Chivalric Symbols of Hermeticism & the Geometry of Time

Originally published in Knights Templar Magazine, Spring 2024. This is the author's original version.

It’s rare to see articles written about geometry in Masonic magazines. Outside the lecture on the middle chamber in the second degree, it’s rare to hear geometry discussed in Lodge, either. Yet, under the surface our ritual is steeped in geometrical symbolism.

It’s not an easy subject to write about. Not everyone is good at math. Not everyone cares about geometry. In the modern world, geometry seems arcane, its foremost mathematicians quaint – even irrelevant – and demonstrating angles, lines and circles, along with rules, postulates and theorems is a surefire way to get most anyone to skip to the next article.

On top of all that, most people took geometry in school and passed, so what else is there to say really? Well, maybe that’s the wrong question. With geometry, maybe it’s more about what is shown, not spoken. So we are going to skip all the talk of Euclid and Pythagoras and jump straight to showing you geometrically how the Maltese and Templar crosses are inseparably interwoven with how we measure time, I believe on purpose.

Some people would call this sacred geometry. Others, nature’s geometry. The reasons for that are many, but you can just call it plain geometry, because at its core that’s all it is.

The first thing we need, as Masonic geometricians, is of course a compass. Our craft revolves around this (no pun intended) and its familiarity to us should be second nature. Why would the compass be so important to us in geometry? Well, because all things in this realm of geometry, even straight lines, begin with circles. Because of their lack of a beginning and an end, they are the ultimate symbol for infinity or eternity. They represent something without end, a vast never-ending expanse. That said, let’s draw.

The Underlying Geometry

The first circle we create can be of any size. What we are doing is universal, and based on proportion, not magnitude, so your circle can be of any radius you like. You can use any unit of measurement you want, or none. Notice that after making this circle with your compass, you actually see the circumpunct, a ‘big-bang’ on paper, as the swivel-end of the compass leaves a hole in the center of the circle where it spun on the paper.

This relationship between the circle and the circumpunct, the symbol of our craft, and creation itself, is a clue we are on the right track.

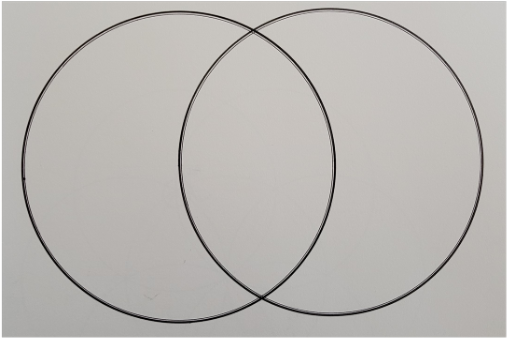

Circle made, we then make our second circle. We must make it the same diameter as the first—symmetry and order—so our compass settings won’t change. Symbolically speaking, circles, arches and any rounded shape are feminine. Conversely, in sacred geometry, straight lines and angles that come to points are considered masculine. (This geometrical symbolism can be extended to nature. For example, in the human phenotype, women are generally more curvy while men are generally more square-shaped and boxy.)

When we overlay the second circle on the first so that their circumferences touch each other’s center, we have created a very famous shape called the vesica piscis. This shape has been studied, written about, and meditated on by philosophers, mathematicians, mystical Christians, Muslims, Jews, Hindus, Buddhists, designers and architects (among others) for thousands of years. So, I’m not going to go much into it here, but just know within these two circles is the information behind the geometry of creation, as it is understood symbolically, both in modern times and ancient.

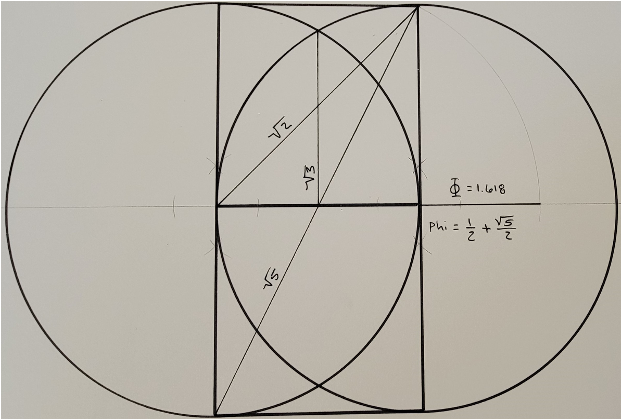

To illustrate only a little bit, in the vesica piscis you can find the square roots of 2, 3, 5, and phi the golden ratio. All those numbers are irrational and all of them are found repeatedly in creation. Because of this they have been used by man to imitate God’s perfection. These ratios were used in the construction of Solomon’s Temple. They were also used in the Sphinx, the pyramids of Giza, and the beautiful cathedrals of Europe.

The ‘almond’ center of the shape itself even resembles that from which all life comes, be it an apple from its seed, or a baby from its mother. For the curious student, there is some very profound information here, but the focus of this article is time and these mystical crosses. So, onward!

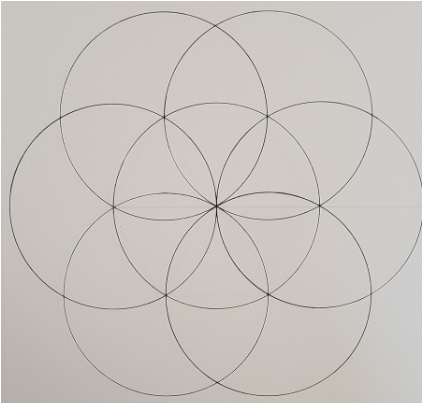

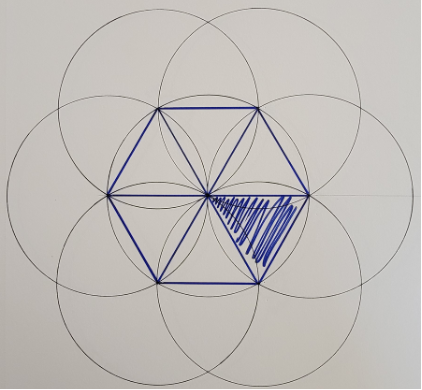

We all know that symbolically, seven is the number of perfection, but we have only made two circles. Let’s make five more. Using the intersections created by the overlapping circles and without changing the diameter of our compass, we place our point and draw five more circles, creating a flower-like design known as the seed of life. The seed of life can be found in holy places all over the world. It’s the symbol of the very measurement and interpretation of time. It is also the symbol at the heart of the crosses we are concerned with here.

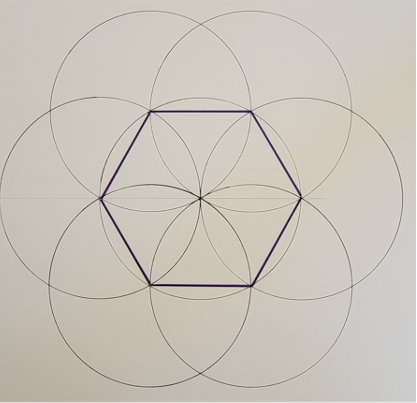

Since we haven’t drawn any straight lines yet, this seed is considered a feminine shape. Like an apple whose root sprouts from its vesica shaped seed—our feminine geometrical shape created—we can now begin to draw out the masculine lines hidden inside. The first obvious masculine shape is the hexagon. It is the six-sided shape made from connecting the tips of the flower petals together.

If we draw straight lines inside the hexagon from one end to the other through the center, we see that the hexagon is made up of six equilateral triangles.

Equilateral triangles, or deltas, have been a symbol of deity for millennia and here in sacred geometry we see its importance as the most basic building block for the hexagon. It is in fact the most basic building block used by all the other platonic solids as well, thus cementing its role as the creative force in all geometry.

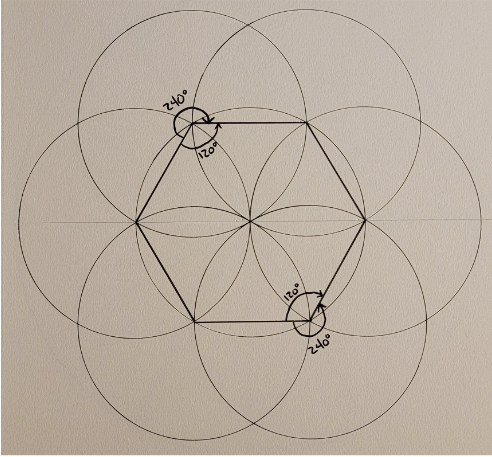

This isn’t just any hexagon, mind you. The angles of this hexagon are directly related to how we measure time. This is where our first hint of the relationship between the knight’s crosses and time’s measure is inferable. The outside angle of this hexagon is 240 degrees. That makes the interior angle 120 degrees.

You can see how the angles of this hexagon hint to us, in hours, the length of a day and its half. Yes, there are six angles in a hexagon, but when you multiply each of those angles by 6 you get the true story of the hexagon. Let’s do that. 6 x 120 = 720 and 6 x 240 = 1,440. What does that have to do with time? In twelve hours there are 720 minutes. In twenty-four hours there are 1,440 minutes. The hexagon is the vessel for the measurement of time.

The Maltese Cross

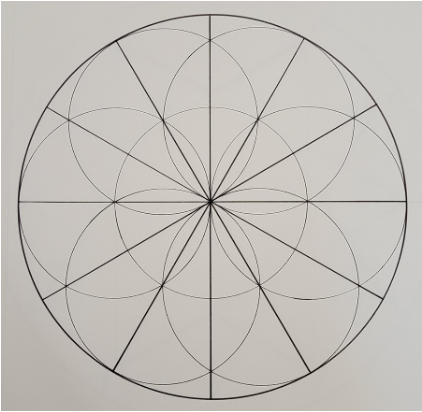

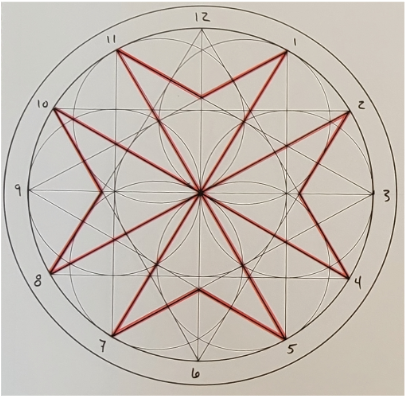

The hexagon isn’t the only masculine shape that can be created from the seed of life. If the seed of life is circumscribed in its own circle and lines are again drawn through the intersections that pass through the center (the same way as before when making the equilateral triangles), the circle is now divided into twelve equal parts, the exact number of parts needed to make a geometrically accurate clock with thirty degrees between each section.

Starting with a circle we went to the vesica piscis. From there, we created the seed of life. Then one more circle to enclose the seed, and with added lines bisecting the intersections of the circles therein contained, we have arrived at the basic design for a clock face.

Here is where I need to mention Hermes, also known as Thoth, also known as Mercury. He was the god of many things, among them commerce, trade and merchants, which put weights and measures under his domain. This will become more relevant as we continue with the geometry, but just remember, Hermes is connected to the measurement of time via his authority over weights and measures.

Our ancient forbears were a mystical bunch. They needed their symbolism not only to hide secrets, but to evoke deity and inspire holiness. So once they arrived at this geometric point, they went straight to drawing equilateral triangles, the geometric creative force and symbol of God. If we draw a straight line from the 12 o’clock position to the 4 o’clock position, from there to the 8 o’clock position, and then back to 12 o’clock where we started, we have created an equilateral triangle. This equilateral triangle cuts the circle into a quarter and, as such, its angles only point to three numbers on the clock. If we rotate this triangle 3 times around the circle (thirty degrees each rotation) so that each number on the clock is pointed to by an angle of a triangle, a twelve-pointed star appears: the design template needed for the Maltese cross.

From here, the Maltese cross can be brought forward by accenting the appropriate lines.

The Maltese Cross is symbolically associable with the measurement of time because the underlying geometric template from whence the Maltese Cross is devised is the same as that of a clockface, or in ancient times, a sundial. This clock, however cool, is about as exact as a sundial and not that sophisticated. Could ancient man have known the length of a second to tell time more accurately? That’s where the Templar cross comes in.

The Templar Cross

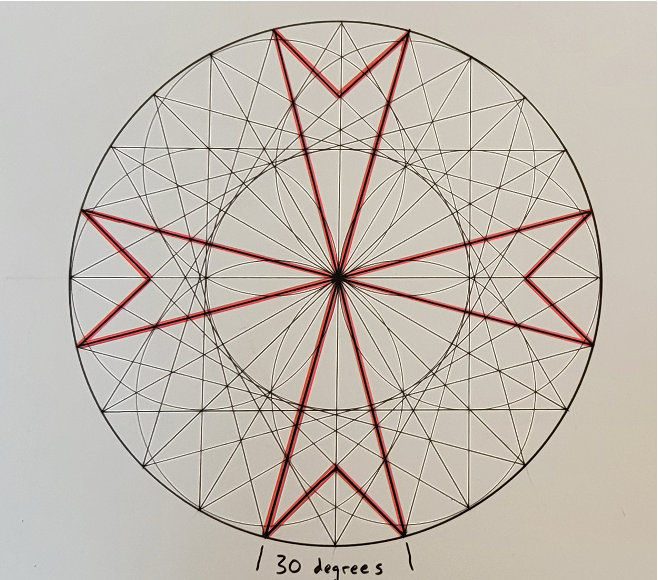

As we saw above, the Maltese cross is based on a twelve-pointed star. As a result, the two points on any arm of the cross are at sixty degrees of each other. To measure the passage of a second, we need to demarcate a 30-degree arc, and we need that 30-degree arc pointing downward in order to mark the interval of a pendulum swung 30 degrees. Ancient man, including the ancient Egyptians, hung a pendulum of a certain length and weight, and swung it in a 30-degree arc to determine the length of a second. The time it took for the pendulum to swing the 30-degree arc was one second.

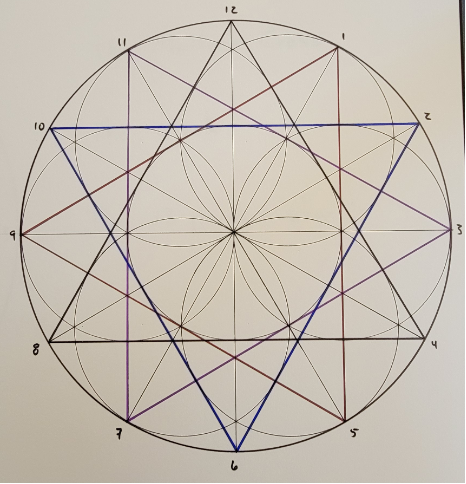

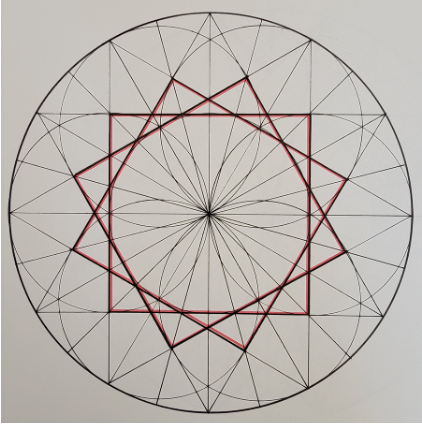

If you look at the Maltese cross we created, there are no thirty-degree markings at the bottom of the circle for us to swing the pendulum. The only angle we have to work with at the bottom of the circle is between the 5 o’clock and the 7 o’clock positions, which is sixty degrees. We can fix that geometrically by bisecting the existing angles in the Maltese Cross template, thereby making a twenty-four-pointed star and the geometry needed for the Templar cross.

Inside the geometrical patterns created in our Maltese template, there is a series of rotating squares, three of them as a matter of fact. I have highlighted them to make them easier to see. If we draw lines from the corners of the squares, bisecting the square through its center, and extend those lines to the perimeter of our design, we will now have subdivided the circle into twenty-four equal parts.

The Templars were esotericists. They imbued their symbols with mysticism. And so, we will create three more rotating equilateral triangles using the endpoints of the lines we just drew. At this point, we have now not only mapped out the points needed for our thirty-degree pendulum swing, but we have also drawn the 24-pointed star geometry needed to create the Templar cross. As with the Maltese Cross, it is now just a matter of shading and darkening lines already created until you get the design you want.

I briefly mentioned above that Hermes is the god of many things, but also of weights and measures. What is it that we’ve talked about here but the measure of time? The Templar and Maltese knights were said to be keepers of the Hermetic secrets. Being able to accurately measure time when most people only had rudimentary means—and then encoding that knowledge in their symbols—a more practical use of the symbols—lends considerable weight to that assertion.

*This article explores the hidden geometry connecting ancient timekeeping to Templar symbols—just one example of the encoded knowledge treasure hunters and historians encounter in their research. For more investigations into archaeological mysteries and treasure legends, subscribe to Buried Expectations and follow along on our YouTube page. If you want to join in the deeper conversation, head on over to our Discord!