The Circle, Part 2: Caleb Cushing

THE DOUGHFACE

In the decades before the Civil War, critics used the term "doughface" to describe a particular kind of politician, a Northerner who served Southern interests. The word was coined by Virginia congressman John Randolph during the Missouri Compromise debates of 1820, mocking Northern representatives who voted with the South as men frightened by their own masks of dough. Webster's Dictionary defined doughfacism in 1847 as "the willingness to be led about by one of stronger mind and will." Historian Leonard Richards classified over three hundred congressmen as doughfaces in the period between 1820 and 1860, including two presidents, Franklin Pierce and James Buchanan, but if there were to be a textbook example of a doughface, it would Caleb Cushing of Newburyport, Massachusetts.

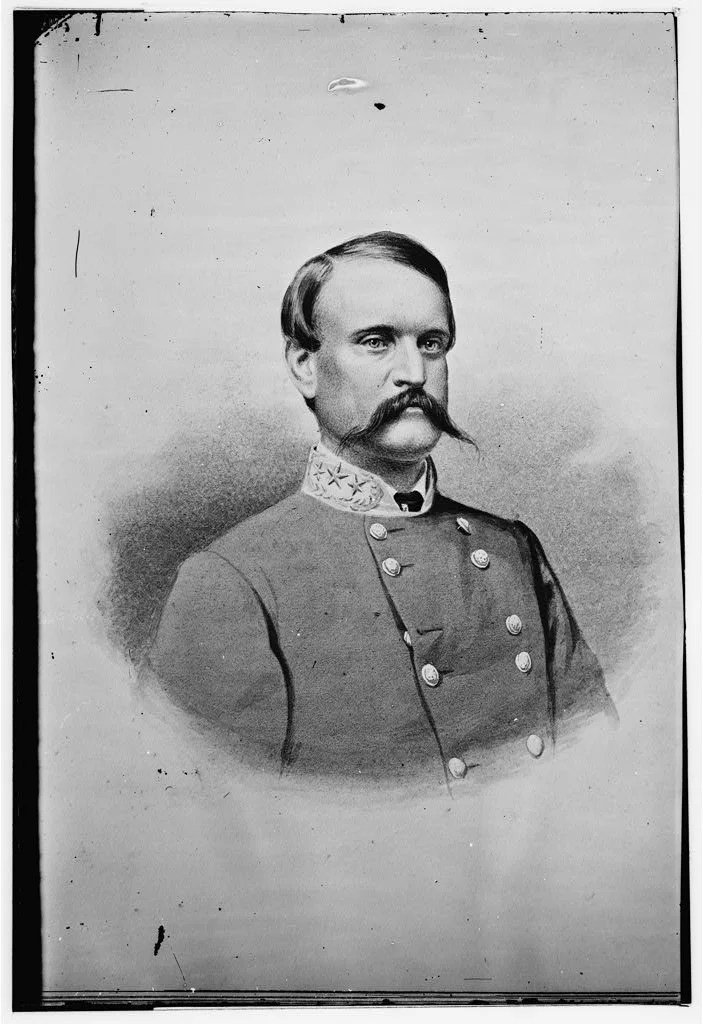

(Caleb Cushing. Photo courtesy of Library of Congress.)

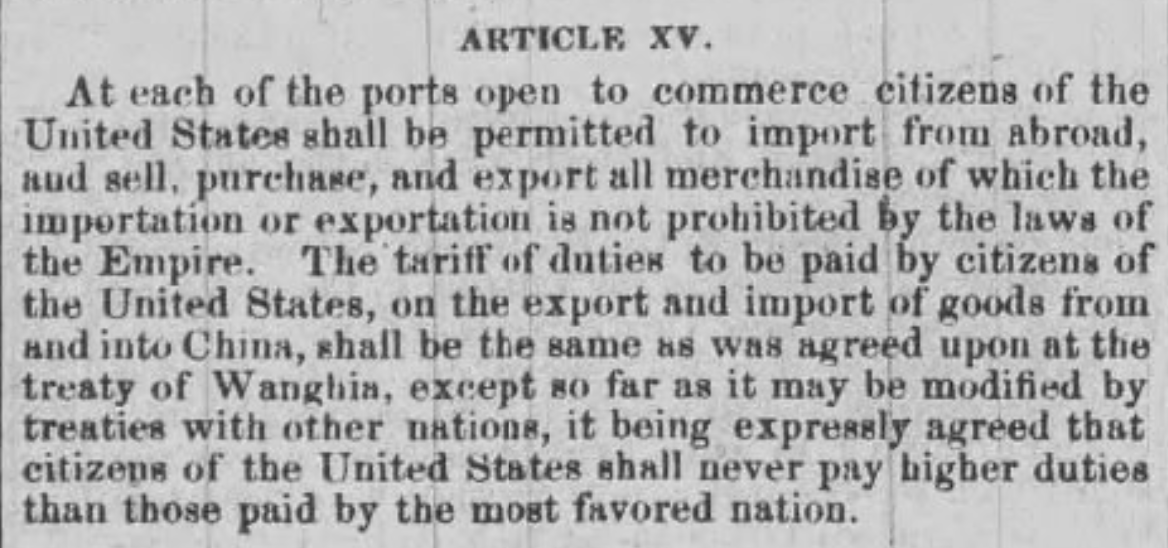

Born in 1800, Cushing entered Harvard at the age of thirteen and was practicing law by twenty-one. He went on to serve in the Massachusetts legislature before winning an election to the United States House of Representatives in 1834, where he sat for four terms as a Whig. When President John Tyler broke with the Whig Party and vetoed its legislation, Cushing was one of the only Whigs to defend the vetoes, a betrayal his party never forgave. Tyler however, rewarded him with a nomination as Secretary of the Treasury, which the Senate rejected three times in one day. So, Tyler then sent him to China, where Cushing negotiated the Treaty of Wanghia in 1844, the first formal agreement between the United States and China. It was an extraordinary diplomatic achievement.

(Article XV of the Treaty of Wanghia. Courtesy Daily National Intelligencer Sep 07, 1860.)

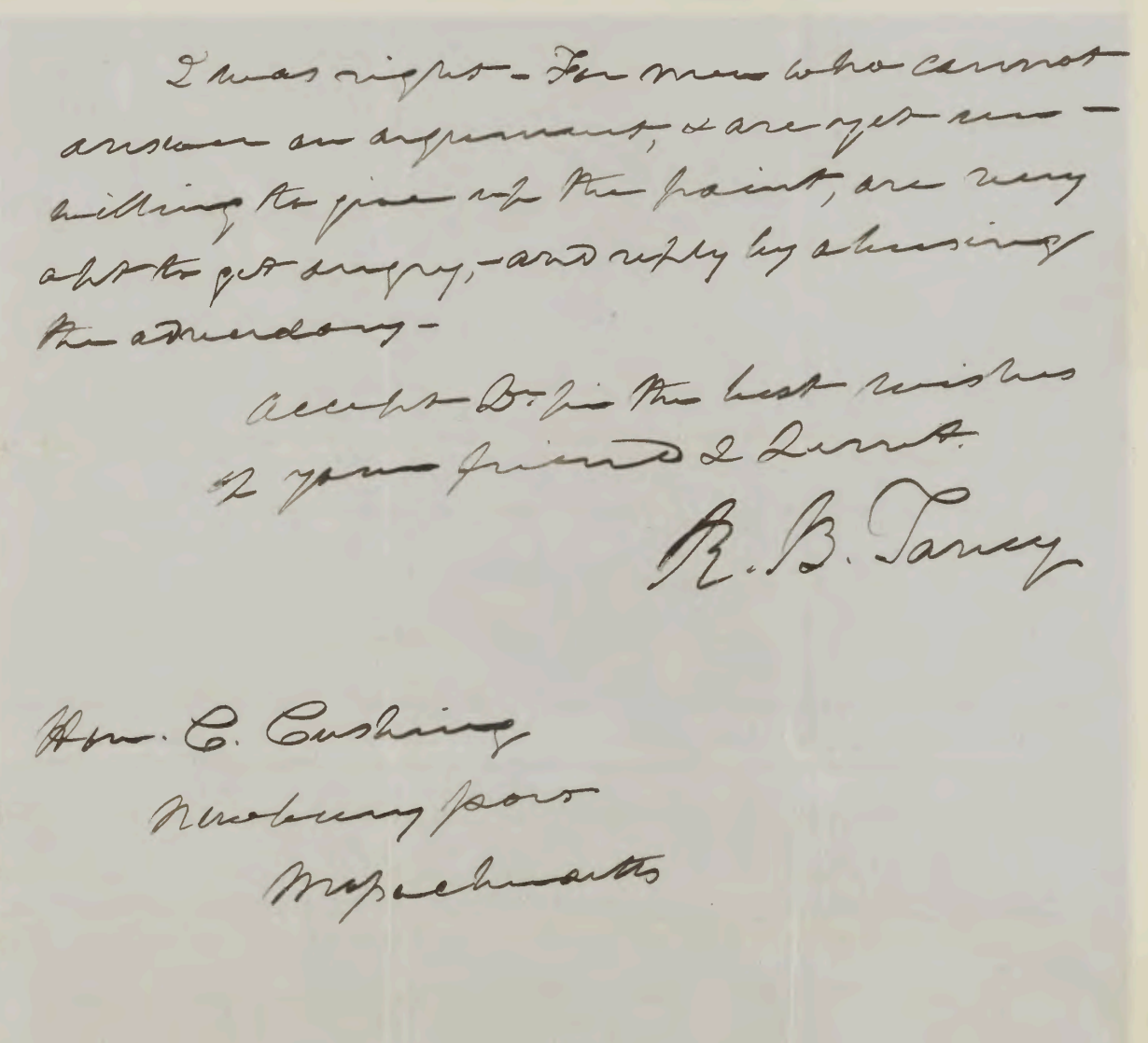

By the 1850s, Cushing had completed his transformation from Whig to Democrat, and not just any Democrat either. President Franklin Pierce appointed him Attorney General in 1853, a position he held until 1857. During those four years, Cushing became a vocal champion of Southern positions on slavery. When Chief Justice Roger B. Taney handed down the Dred Scott decision in March 1857, ruling that African Americans were not citizens and that Congress had no power to prohibit slavery in the territories, Cushing delivered a major speech in Newburyport defending the decision and praising Taney as "the very incarnation of judicial purity, integrity, science and wisdom." The Chief Justice was so grateful for this northern support that he personally wrote Cushing a letter of thanks on November 9, 1857, noting that the "public mind was not in a condition to listen to reason" and that "wild passions ruled the hour."

(A portion of the letter from Justice Taney to Cushing. Courtesy Library of Congress.)

THE 1860 CONVENTION — SPLITTING THE NATION

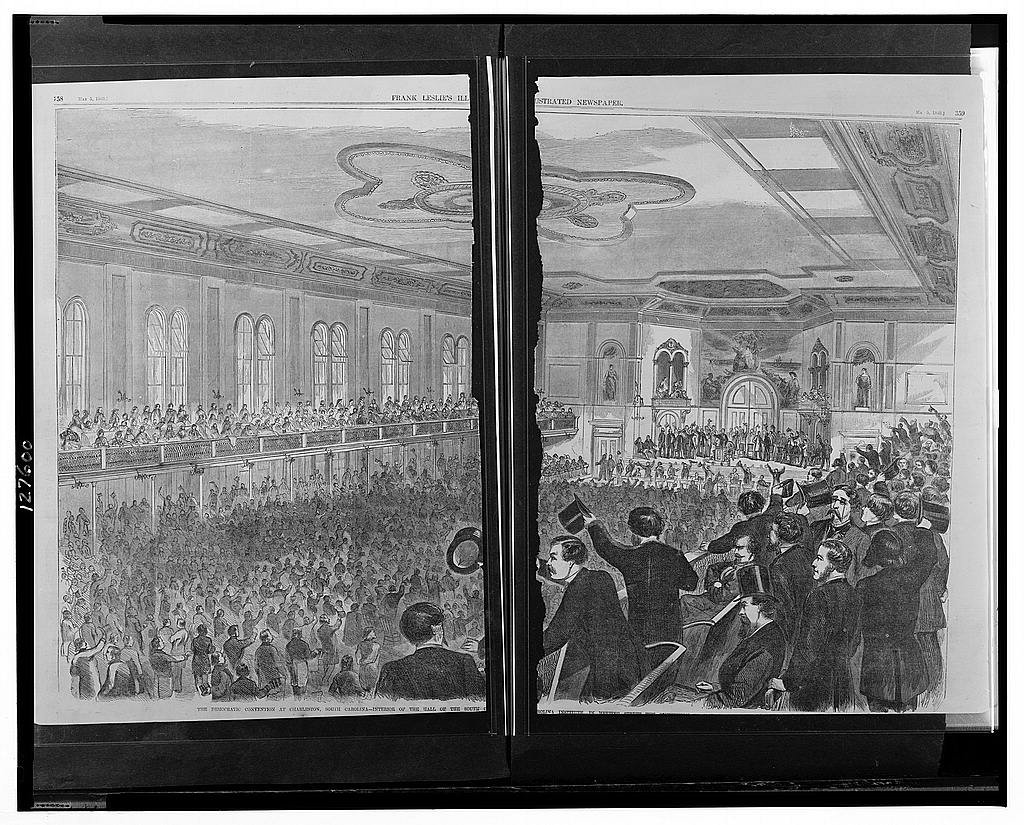

In April 1860, the Democratic Party convened at the South Carolina Institute Hall in Charleston to nominate its candidate for president. The galleries were packed with pro-slavery spectators. Stephen A. Douglas of Illinois was the clear front-runner among Northern Democrats, but the militant Southern faction known as the "Fire-Eaters," led by William Lowndes Yancey of Alabama, had no intention of letting him win. They demanded a platform explicitly endorsing the Dred Scott decision and federal legislation protecting slavery in all territories. Douglas and the Northern delegates refused. The man presiding over this collision was Caleb Cushing.

(The Democratic Convention at Charleston, South Carolina - Interior of the Hall of the South Carolina Institute, Frank Leslie's illustrated newspaper, v. 9, no. 231 (1860 May 5), pp. 358-359, Courtesy Library of Congress)

Elected permanent president of the convention on April 24, Cushing occupied the most powerful procedural position in the room, and he used that power to his political advantage. When the convention moved to nominations, Cushing ruled that a candidate needed two-thirds of the entire convention membership to win, not two-thirds of those present and voting. Fifty-one Southern delegates had already walked out over the platform dispute. Under Cushing's ruling, their empty seats still counted against Douglas. The result was fifty-seven ballots over two days, with Douglas winning a majority on every single one, but never reaching the impossible threshold Cushing had set. The convention adjourned in failure, and it was the first time in Democratic Party history that a convention had been unable to nominate a candidate.

When the Democrats reconvened in Baltimore that June, the crisis deepened. The credentials committee voted to seat replacement delegates for some of the states that had bolted in Charleston. In response, nearly all the remaining Southern delegates walked out again, and this time, Cushing went with them. The chairman of the Democratic National Convention, a man from Massachusetts, abandoned his own party's convention and followed the Southern secessionists out the door. After walking out, Cushing walked straight to Baltimore's Maryland Institute Hall, where the delegates had reassembled. He took the chair and presided as this rump convention adopted the pro-slavery platform that had been rejected at Charleston, and he presided as they nominated Vice President John C. Breckinridge of Kentucky for the presidency.

Breckinridge was no mere Southern sympathizer. A U.S. Army officer who infiltrated a KGC council of war in November 1860 identified Breckinridge as a member of the order alongside Secretary of War John Floyd and Secretary of the Treasury Howell Cobb. The 1861 Exposé of the Knights of the Golden Circle, now held at the Library of Congress, describes the Breckinridge presidential campaign itself as a KGC operation and details a plan to capture Lincoln in Baltimore, seize Washington, and install Breckinridge as president. Historian David C. Keehn has since documented how the KGC functioned as the organizational backbone of Breckinridge's candidacy before transforming into a pro-secession paramilitary fifth column. It has also, been reported, but with unverifiable sourcing, that Breckinridge would wear a KGC emblem, a Maltese cross superimposed on a star, as a lapel pin in Washington.

Like Cushing, who was a member of St. John’s Lodge in Newburyport, Breckinridge was also a Freemason. He was a member of the Grand Lodge of Kentucky and the first Sovereign Grand Inspector General of the Scottish Rite in his state, chartered in 1852 under the same Supreme Council that Albert Pike would command seven years later. The man Cushing nominated from the chair of that splinter convention would, within two years, become a Confederate general and ultimately the Confederacy's Secretary of War. The Norfolk Virginian, looking back on these events in 1874, described Cushing plainly: he was the man who "seceded from the chair" of the regular convention, "presided over the bolting Fire-eaters' convention," and was a "supporter of that rebel ticket in the eventful Presidential campaign which followed."

(John C. Breckenridge, Confederate States of America. Courtesy of Library of Congress.)

The consequences were exactly what one might expect. Or, as historian James McPherson has suggested, exactly what the Fire-Eaters intended. With the Democratic vote split between Douglas in the North and Breckinridge in the South, Abraham Lincoln won the presidency with less than forty percent of the popular vote. Within months, Southern states began to secede. The Civil War was on.

Whether or not Cushing understood the full implications of his actions at Charleston and Baltimore is a question historians have debated. It’s hard to debate the record however. He used his procedural authority to block Douglas. He walked out with the South. He nominated a suspected KGC member who would become a Confederate officer, and on March 23, 1861, weeks after Southern states had begun forming the Confederacy, Cushing sat down and wrote a letter directly to Jefferson Davis, President of the Confederate States of America. In the letter he recommended a man defecting from the North, Archibald Roane, as someone the Confederacy could trust. That letter would surface thirteen years later and destroy his nomination for Chief Justice of the United States.

THE PIKE CONNECTION

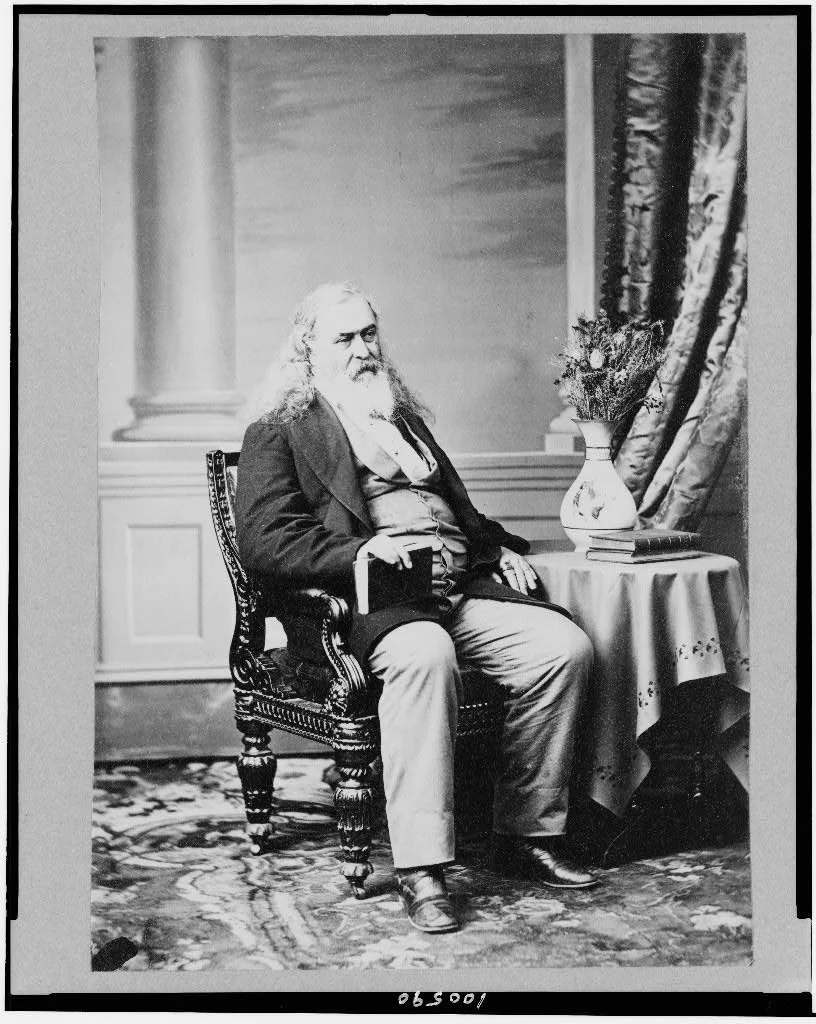

In the years before the Civil War, few men held more power in the American South than Albert Pike. Born in Boston in 1809, Pike grew up in Newburyport, Massachusetts, the same small shipping town where Caleb Cushing was from. Pike attended schools there through the age of fifteen and even passed the Harvard entrance exam but could not afford tuition. He taught at the Newburyport Grammar School and eventually headed west in 1831 to seek his fortune, settling in Arkansas. From there he became a prominent attorney, practiced before the United States Supreme Court, and served as a cavalry officer in the Mexican - American War.

(New York Tribune, Aug 17, 1859.)

In 1859, Pike was elected Sovereign Grand Commander of the Scottish Rite's Southern Jurisdiction, the highest leadership position in the southern branch of American Scottish Rite Freemasonry. He would hold that title for the remaining thirty-two years of his life. When the Civil War came, Pike cast his lot with the Confederacy. Commissioned as a brigadier general, he was appointed Confederate Commissioner of Indian Affairs, negotiating treaties of alliance with the Cherokee, Creek, Choctaw, Chickasaw, and Seminole nations. Afterward he took command of the Department of Indian Territory. His wartime service ended in controversy, including charges of insubordination and treason, though these were eventually dropped. After the war, Pike was pardoned by President Andrew Johnson, restoring his citizenship after being a former Confederate officer, and spent his final decades in Washington, D.C., living and eventually dying at the Scottish Rite Temple.

Pike's connection to the Knights of the Golden Circle is a matter of historical dispute, for the obvious reason that secret societies do not publish membership rolls. What the historical record does show is this: the 1861 Exposé of the Knights of the Golden Circle documents active KGC castles operating in New Orleans during the period when Pike was living and practicing law in that city. The KGC's organizational structure borrowed heavily from Masonic models, using lodges they called castles, secret signs of recognition, and hierarchical degrees that are very similar to the Masonic degrees. Pike himself was the Grand Commander of the Southern Jurisdiction of the Scottish Rite. He wrote the ritual degrees of that system. He was a Confederate general who through his alliances with Indian nations, operated across a vast territory, including in regions with documented KGC activity. The 1861 Exposé describes a KGC organization built on exactly the kind of Masonic infrastructure Pike controlled. Researchers and historians from Getler's and Brewer’s Rebel Gold to the Texas State Historical Association have listed Pike among suspected members.

Among researchers who study the KGC's post-war activities, Pike's name surfaces repeatedly, not only as a suspected member, but as the rumored architect of the organization's depository system. The theory holds that because the KGC's codes and ciphers drew so heavily on Scottish Rite Masonic symbolism, and because Pike was the supreme authority on that symbolism, he must have been the mind behind the KGC system. The circumstantial logic, however, is difficult to dismiss: the man who literally wrote the rituals of Scottish Rite Freemasonry would have been uniquely qualified to design a coding system built on those same rituals.

(Albert Pike. Courtesy of Library of Congress.)

Pike’s connection to Caleb Cushing however is not up for debate. The finding aid for the Cushing Papers at the Library of Congress lists Albert Pike among Cushing's correspondents, alongside Jefferson Davis, Rufus Choate, Franklin Pierce, and Daniel Webster. It appears that these two men from the same Massachusetts town were in communication each other across the decades that preceded and followed the Civil War.

Their relationship became visible to the public in the winter of 1873-1874. In January 1873, the Daily Arkansas Gazette reported on a United States Senate election in Arkansas in which a Mr. Cunningham, explaining his vote, described the kind of statesman he believed the Senate deserved, "a name that stood alongside that of Reverdy Johnson, Albert Pike and Caleb Cushing," men who "in better days had adorned the state in the national council.” One year later, the two were to appear together as the featured speakers at a convention of the Associated Veterans of 1846, the organization of Mexican War veterans, held at the Masonic Temple in Washington D.C. The Washington Chronicle announced that Cushing would deliver the oration and Pike would read an original poem. The Council Bluffs Weekly Nonpareil confirmed the pairing: "These two will take a leading part in the ceremonies, Caleb Cushing delivering an address to the veterans, while Albert Pike will read an original poem." The convention planned to proceed from the Masonic Temple to the White House to pay its respects to the President.

(Washington Chronicle Dec 15, 1873)

(Albert Pike’s famous Scottish Rite treatment, Morals and Dogma.)

THE NETWORK

The finding aid for the Cushing Papers at the Library of Congress reads like a map of mid-nineteenth-century American power. Among the correspondents listed are Jefferson Davis, Albert Pike, Franklin Pierce, Daniel Webster, Rufus Choate, Roger Brooke Taney, Hamilton Fish, and William Henry Seward. Presidents, Supreme Court justices, cabinet officers, senators and diplomats, Cushing corresponded with men on every side of every major conflict of his era and maintained relationships with most of them simultaneously.

Cushing, Pike, and Choate all came from the same narrow strip of the Massachusetts coast. Cushing grew up in Newburyport. Pike grew up in Newburyport. Choate was born in Ipswich, barely ten miles away, and practiced law in the same circles. These men came from the same small world, attended the same institutions, belonged to the same fraternities, moved through the same professional channels, and then scattered across the country into positions of extraordinary influence. Cushing became Attorney General of the United States. Pike became Sovereign Grand Commander of the Scottish Rite's Southern Jurisdiction and a Confederate general. Choate filled Daniel Webster's senate seat and became one of the most celebrated trial lawyers of his generation. Rantoul served in congress and argued landmark cases before the Supreme Court. These men represented legal, political, military, and fraternal power at the highest levels of the American system, and they all came from the same corner of Massachusetts.

Cushing sat at the center of this web. In 1860, James Buchanan sent Cushing to Charleston as a confidential commissioner to the secessionists of South Carolina, tasking him with negotiating the crisis over federal forts in Charleston Harbor. Consider what that assignment reveals. The man who had just presided over the convention that split the Democratic Party, who had walked out with the Southern delegates, who had nominated a future Confederate officer for president, was now the administration's chosen envoy to the secessionists in South Carolina. Buchanan did not send Cushing because he was a neutral diplomat. He sent Cushing because the secessionists would open the door for him. A neutral negotiator would have been ignored, and Cushing was clearly not neutral. He was trusted by the Southern leadership precisely because he was one of them, the only difference being, he had Northern credentials.

THE WESTERN EMPIRE

In August 1845, while still a sitting congressman, Cushing organized the St. Croix and Lake Superior Mining Company with two of his Massachusetts associates: Rufus Choate and Robert Rantoul Jr. The stated purpose was copper mining along the St. Croix River in what was then Wisconsin Territory, hundreds of miles from the nearest Eastern railroad. In September 1846, Cushing traveled to the site himself. On October 1, he purchased the assets of the St. Croix Falls Lumber Company outright, acquiring preemption rights, lands, mills, a dam, buildings, and machinery. A new company was immediately organized with Rantoul as president, George W. Brownell as mining and land agent, and H.H. Perkins as lumber agent. Cushing, characteristically, held no title. He remained behind the scenes, the investor and strategist whose name appeared on the capital, but not on the letterhead.

The venture was never really about copper. The mining company produced little ore and less profit. What it did produce was a claim to territory, and Cushing moved quickly to protect it. As Wisconsin prepared for statehood in 1846 and 1847, Cushing, Choate, and Rantoul lobbied to redraw the proposed western boundary of the new state. Their goal was to exclude the St. Croix Valley entirely, leaving it in unorganized territory that could be carved into a new jurisdiction with Cushing as its governor. The effort partially succeeded. The St. Croix River became Wisconsin's western boundary instead of the originally proposed Rum River, a shift that kept the valley on the edge of state authority even if it remained within Wisconsin's borders. The full separation Cushing envisioned never materialized, but the political maneuvering revealed the scale of his ambition.

The mining company eventually failed, but Cushing did not leave. Over the following decade, as Rantoul and Choate turned their attention elsewhere, Cushing quietly consolidated. In 1854, the same year he took office as Attorney General, he established the Cushing Land Agency to manage and sell his St. Croix holdings. In 1857, he won a court case that secured the vast majority of the land at St. Croix Falls. By February 1, 1861, when he prepared a formal financial statement of his holdings, Cushing owned one quarter of all shares in the St. Croix Manufacturing and Improvement Company. The greater part of the remaining shares were held by residents of Washington, D.C., including the company's president, Samuel C. Edes. What had begun as a mining venture among Massachusetts lawyers had become a land empire controlled from the nation's capital.

It was at this moment, with sixteen years of infrastructure in place, that a Norwegian lawyer entered the picture. In 1857, James DeNoon Reymert had been appointed receiver of the land office at Hudson, Wisconsin, later transferred to St. Croix Falls. According to Alice E. Smith's research into the Cushing Papers, Reymert envisioned filling the valley with Norwegian immigrants and discussed plans with Cushing for “similar colonization of the Wisconsin side.” By October 1861, Reymert was writing to Cushing from the Astor House in New York, awaiting his arrival and eager to present "some plans, which, if I can execute, will be of very great benefit to your interest in the Southwest," adding that should Cushing approve, he would "hasten back to carry them out."

(Letter from Reymert to Cushing concerning Cushing’s plans for the Southwest. Cushing Papers. Box 354. Folder 1.)

The Waukesha Freeman reported in 1873 that Reymert's "professional connection and business with the Hon. Caleb Cushing and other Eastern eminent jurists brought him often to New-York, and in 1861 he removed to this city." The Minneapolis Journal was more direct. In its 1896 obituary of Reymert, it stated plainly that "Caleb Cushing induced Reymert to go to New York to practice law."

(Reymert was sent to New York by Cushing. The Minneapolis Journal. April 24, 1896.)

Reymert, it seems, did not relocate to New York on his own initiative. He went because he was “induced” by Cushing. Reymert was no random associate. He was a Norwegian immigrant with Scottish - Sinclair, blood, a lawyer trained in Edinburgh, a Masonic Knight Templar, a frontier newspaper editor, and a territorial politician who had been Cushing's business partner across multiple ventures for over a decade. Who he was, where he came from, and what the two of them built together is where our story turns next.

Sources

• Leonard L. Richards, The Slave Power: The Free North and Southern Domination, 1780–1860 (Louisiana State University Press, 2000).

• "Doughface," Webster's Dictionary (1847).

• Letter, Roger Brooke Taney to Caleb Cushing, November 9, 1857, Library of Congress.

• Claude M. Fuess, The Life of Caleb Cushing (Harcourt, Brace and Company, 1923).

• Official Proceedings of the Democratic National Convention, 1860, Library of Congress.

• James M. McPherson, Battle Cry of Freedom (Oxford University Press, 1988).

• Norfolk Virginian, January 15, 1874.

• Bruce Catton, The Coming Fury (Doubleday, 1961).

• Walter L. Brown, A Life of Albert Pike (University of Arkansas Press, 1997).

• Robert L. Duncan, Reluctant General: The Life and Times of Albert Pike (E.P. Dutton, 1961).

• Caleb Cushing Papers, Library of Congress.

• Daily Arkansas Gazette, January 19, 1873.

• Washington Chronicle, December 1873.

• Council Bluffs Weekly Nonpareil, January 21, 1874.

• An Exposé of the Knights of the Golden Circle (Indianapolis, 1861), Library of Congress.

• Warren Getler and Bob Brewer, Rebel Gold (Simon & Schuster, 2004).

• "Caleb Cushing," MasonryToday.com.

• Alice E. Smith, "Caleb Cushing's Investments in the St. Croix Valley," Wisconsin Magazine of History 28, no. 1 (September 1944).

• "James D. Reymert," Waukesha Freeman, 1873.

• David C. Keehn, Knights of the Golden Circle: Secret Empire, Southern Secession, Civil War (Louisiana State University Press, 2013).

• "Avowed Enemies of the Country," HistoryNet, May 17, 2017.

• Devin Thomas O'Shea, "Knight Club," History News Network, January 14, 2025.

• Kentucky Historical Marker, "Scottish Rite Temple," Louisville, Kentucky.

• "Death of J.D. Reymert," The Minneapolis Journal, April 24, 1896.

• Letter, James DeNoon Reymert to August Reymert, November 1876, Norwegian-American Historical Association.

• Letter, Jeanette Sinclair Reymert to James DeNoon Reymert, August 14, 1839, Norwegian-American Historical Association.