The Tucson Silverbell Artifacts: Part 3 - The Confession

POTENTIAL PERPETRATORS

THE SUSPECTS

If, and I did say if, the artifacts are a hoax then the question becomes: who made them, and why? Over the past century, several candidates have been proposed. Each has circumstantial evidence in their favor, and none has been definitively proven. The identity of the possible forger, remains, even now, an open question.

Timoteo Odohui

The earliest suspect was a young Mexican sculptor named Timoteo Odohui, whose family lived at the lime kiln site during the 1880s. His father, Vicenti Odohui, had reportedly fled Mexico after the Franco-Mexican War and settled his family near the kilns along Silverbell Road. According to interviews conducted in 1926 with a retired cowboy named Leandro Ruiz, the younger Odohui was known for working with soft lead alloy and possessed a large personal library that included texts in Hebrew and Latin. Ruiz recalled that Odohui had made various lead objects, including a marker commemorating a horse-fall injury Ruiz had suffered.

The Odohui theory accounts for the location. Someone living at the lime kiln would have intimate knowledge of the site and access to the raw materials needed to manufacture artificial caliche. It also accounts for the lead working and the multilingual inscriptions, assuming the library Ruiz described was as extensive as he remembered decades later. But the theory has a significant weakness in its timeline. If Odohui created the artifacts in the 1880s, they would have sat in the ground for roughly forty years before Manier stumbled across them in 1924. What was the motive for a young sculptor to bury elaborate lead crosses in the desert with no audience and no prospect of discovery? The Odohui family left Tucson and was never seen again in the local area, and so, nobody has been able to track them down.

(Artifact 6a. Photo by Joseph Miele)

Clifton Sarle and Charles Manier

A more frequently discussed theory points to two men who were directly involved with the artifacts from the beginning: Clifton Sarle and Charles Manier himself. Sarle was a geologist who had been fired from the University of Arizona three years before joining the excavation team. The university had praised him as "an excellent field geologist" while simultaneously letting him go for "not being well suited to teaching." According to the theory, his termination left him with both the knowledge and the motive to embarrass the institution that had dismissed him. As a geologist, Sarle understood caliche formation well enough to know how to fake it. As someone with a grievance against the university, he had reason to want its faculty to stake their reputations on something that would later prove to be a fraud.

Manier, meanwhile, was the man who made the initial discovery and brought in both Thomas Bent and Sarle. Speculation that the discoverers themselves perpetrated the hoax has existed since the artifacts first surfaced. It is a common pattern in archaeological fraud, the person who finds the objects is often the person who planted them. Don Burgess, in his 2009 article, also speculated that the hoax may have begun as a prank intended to embarrass the University of Arizona, conceived by Sarle and executed with Manier's help. The scheme may have spiraled beyond their original intentions once Cummings threw his support behind the artifacts and the university offered $16,000. What started as a joke became an opportunity, and what became an opportunity, became a trap; Too far along to confess, too invested to walk away.

Thomas Bent, by this reading, was not a conspirator but a victim. He was the true believer who homesteaded the site, moved his family onto the property, spent decades of his life and considerable personal resources defending the artifacts, and eventually produced a 350-page unpublished manuscript arguing for their authenticity. If Sarle and Manier created the hoax, Bent was the man they deceived most thoroughly.

The Mormon Question

There is one additional possibility that has received less attention, but I believe merits consideration. The artifacts display a combination of religious and cultural symbols, Christian crosses, Jewish menorahs, Hebrew inscriptions, Latin text, and Masonic symbols including the square and compass on Artifact 20, that is difficult to attribute to any single historical community. There is one group in the American Southwest however, whose theological background encompasses exactly this combination of traditions: the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

A Mormon Battalion, comprising over five hundred soldiers, marched through Tucson in December 1846 and camped for several days along the Santa Cruz River during the Mexican American war, the same river corridor where the Silverbell Road lime kilns are located. Later, Mormon settlers began establishing permanent communities in Arizona during the 1870s, and by the 1880s, the period when the artifacts were most likely fabricated if they were in fact fabricated, there was a substantial established Mormon presence in the territory.

(Artifact 6b. Photo by Joseph Miele)

The theological connections are worth noting. The Book of Mormon's central narrative involves ancient peoples from the Old World migrating to the Americas, precisely the claim the Tucson artifacts make. Joseph Smith, the founder of the church, was himself a Freemason (eventually), and early Mormon leadership had extensive Masonic knowledge. Mormon temple ceremonies historically incorporated symbolism drawn from Masonic ritual, including elements that overlap with imagery found on the artifacts, like the square and compass. A person steeped in Mormon theology would possess the symbolic vocabulary needed to create objects that blended Christian, Jewish, and Masonic imagery in exactly the way the Tucson artifacts do.

Int his theory, the motive would be straightforward: fabricated artifacts proving that ancient Old World peoples had migrated to the Americas would corroborate the Book of Mormon's historical claims. Joseph Smith himself had presented physical artifacts, the golden plates, as evidence of an ancient American civilization with Old World roots. The Tucson artifacts, if accepted as genuine, would have served a similar function.

This theory is speculative, and no direct evidence links any specific Mormon individual to the creation of the artifacts. It is just my analyzation of the symbols on the artifacts, using my knowledge as a Mason myself, to try and sus out some meaning from the carvings on the lead artifacts, but the geographic proximity, the timeline, the symbolic overlap, and the theological motive make it a possibility that I do not entirely dismiss.

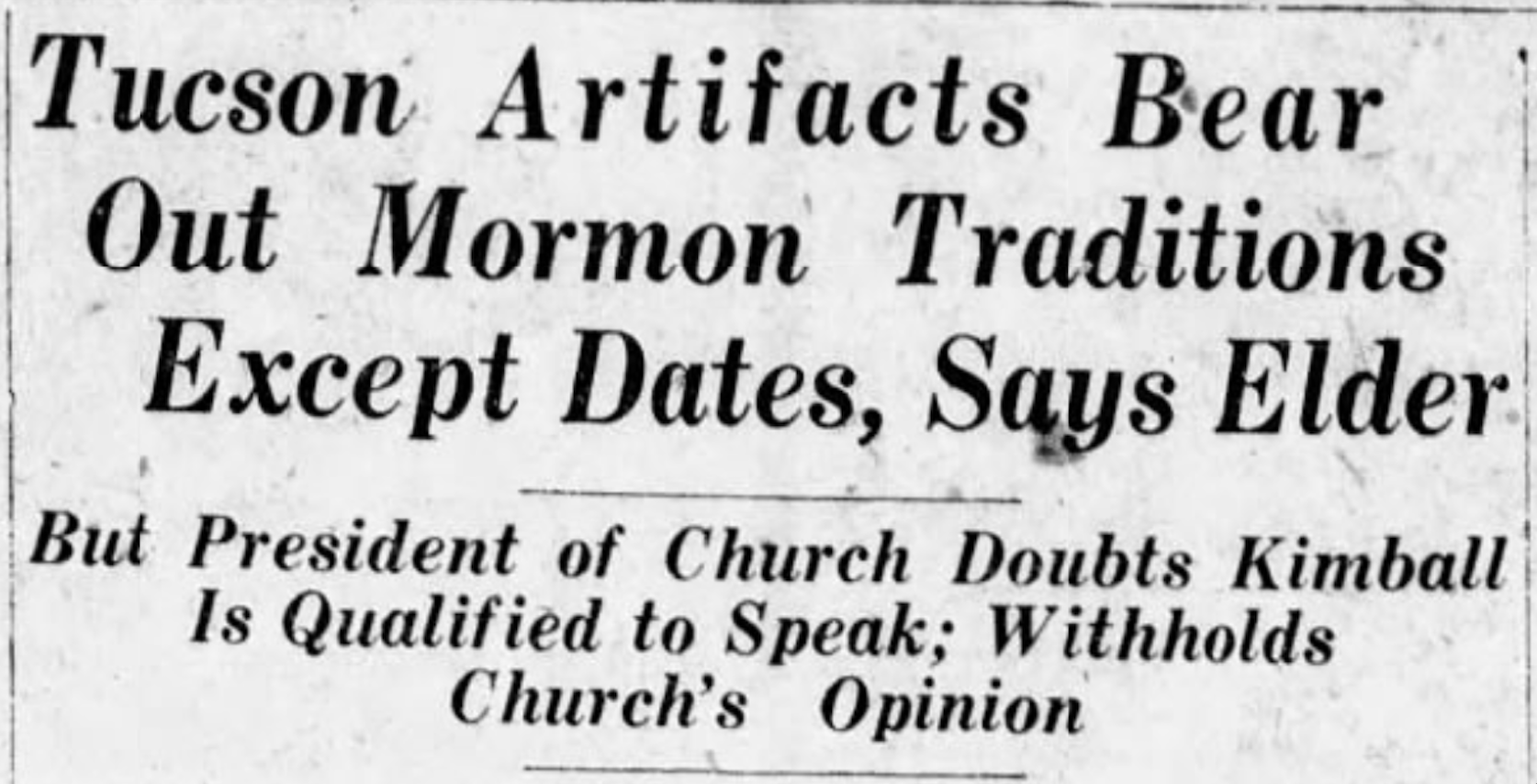

(Newspaper headline from the Arizona Daily Star, Dec. 16 1925)

THE BESSIE MANIER CONFESSION (1973)

In the archives of the Arizona Historical Society, tucked among the Bent family papers, there is a letter that either solves this century-old mystery or adds another layer to it. The letter is dated May 10, 1973, written by Bessie Lee Manier, the widow of Charles Manier, the man who pulled the first cross from the ground in 1924. It was addressed to Alma Bent, the widow of Thomas Bent, who had died the previous year. Charles Manier himself had been dead since 1941, thirty-two years before Bessie put pen to paper. Enclosed with the letter was a document Bessie presented as a confession.

The cover letter read:

I found this in Some Papers that I was looking throw. I thought you like to have it, Show It to little Tommy so he wont spend Any more money on them, and not be able to get Anything out of it. I try To fine the other Papers. I been Sick with the flu But Am Better now, by by. Your Old Pal Bessie Lee

The enclosed confession, misspellings and all, attributed to Charles Manier and Clifton Sarle, described how the artifacts had been made:

"To Whm this May Concern. Dr Sarls and Charles E. Manier had made The Artifaces, And this is how it was done. First we made a Wooden fram of Crosses. Then Made some spear & swords & Broken Sword & handles. We then went to the junk yard and found some old Lead and Melted it on my kitchen Stove. We drilled The holes in the Colicha Walls. And Save The Colicha sand, that came out of the strata of the wall, we then mixed Cement with the sand and after the crosses were made we poured the lead in the wood fram. And the Words on Crosses Were taken from U of A Library from old book, Laten & Rome Jewish & Mormon and Greek. the letter OL is Oh Lord, I made that up. We hope to prove That the U of A did not know how Long thing Were in the ground, Also the stones on the Back of Crosses were from the Kress store from Ring I bought there they assy were Silver Dime & gold from Rings to Make It Look old, we show this to the U of A And had the Laten translated But was not able to tell the Story that Was on the Artifacts. Now this is a true Confession of Dr. Sarl and Myself I wanted to tell Tom My Friend about them But I hated to hurt his feeling that why I never question Tom about the Artifacts. I let him keep them in His position to see what would Come from them we had chance to Sell them But Tom thought these Were more Value then was offered. This is true I hope the one that fines this tell Tom about There are 3 copies of this out so. Please forgive me if I caused Any trouble. Yours Sencerly Dr SArls & Charles E Manier. Pima Place home was where thy were made C.M.

The confession letter admitted to making frames for molds. Lead from a junkyard was melted on a kitchen stove. Holes were drilled into the caliche walls at the site with the excavated caliche sand saved and mixed with cement to create an artificial seal around the planted objects. Inscriptions were copied from old books at the University of Arizona library, "Laten & Rome Jewish & Mormon and greek." Stones on the backs of the crosses were purchased from the Kress five-and-dime store, taken from cheap rings. Silver dimes and gold from rings were mixed in to make the lead look old. The artifacts were made at "Pima Place home," and the purpose: "We hope to prove That the U of A did not know how Long thing Were in the ground." The letter confesses a prank aimed at embarrassing the university, carried out by a man the university had recently fired.

Several of these details align with what the forensic evidence already tells us. The lead came from scrap, Chapman identified it as type metal, Killick and Thomas confirmed industrial origin. The caliche could have been artificial. Quinlan's experiment proved it could be manufactured in days using exactly the kind of materials described in the confession. The Latin was copied from reference books.

Then there is the detail about "OL." The letters "OL" appear at the end of inscriptions on several of the crosses. For decades, researchers debated their meaning. Cyclone Covey, writing in 1975, and Florence Hawley, writing in 1928, both proposed that "OL" stood for the initials of Laura Ostrander, the Tucson teacher who transcribed the inscriptions. The confession offers a different explanation: "the letter OL is Oh Lord, I made that up."

The confession also addresses Thomas Bent directly. "I wanted to tell Tom My Friend about them But I hated to hurt his feeling that why I never question Tom about the Artifacts. I let him keep them in His position to see what would Come from them." If true, Bent was not a co-conspirator, as previously stated. He was the one person most thoroughly deceived. If the confession is true, then a hoax consumed his life.

There are problems with the confession however, and they are not small ones. Both the cover letter and the enclosed confession are written in the same handwriting, Bessie's. The confession is not a document written by Charles Manier and Clifton Sarle. It was written by Bessie, thirty-two years after Charles's death. Was she transcribing an older document she had found among Charles's papers, as her cover letter suggests? Or was she composing it herself, for reasons of her own?

On July 10, 1973, Alma Bent responded. Her reply was brief and pointed:

Thought I had written you that I had received that Statement you sent me. That statement is sure something and as you know the facts are far from true. Sorry but I think I understand the reason for it. Will just file it away for future reference.

Alma seems to have rejected the confession outright. The facts, she said, were "far from true," but then she added a line that has puzzled researchers ever since: "I think I understand the reason for it." What reason was that? Was Alma protecting the Bent family's legacy and the decades her husband had invested in the artifacts? Did she know something about Bessie's motives that made the confession suspect? Or did she simply refuse to accept that her husband's life work had been built on a lie?

The confession obviously raises as many questions as it answers. Why did Bessie wait thirty-two years after Charles's death to produce it? All the principals were gone by 1973. Charles had been dead since 1941. Sarle was also long gone. Thomas Bent dead since 1972. Was it safer to confess when no one was left to contradict her? Was she trying to prevent "little Tommy," Thomas Bent Jr., from spending more money on what she knew was a lost cause? Was she clearing her conscience at the end of her life? Or was an elderly widow, decades removed from the events, fabricating a story for reasons we may never fully understand?

If the confession is genuine, it effectively narrows the suspect list to two men: Charles Manier and Clifton Sarle. The Timoteo Odohui theory, which places fabrication in the 1880s, doesn't fit a confession describing a 1920s operation using the university library and local stores. The Mormon theory, which requires fabrication by someone with specific theological knowledge, doesn't align with Bessie's account of two men working with junkyard lead and a kitchen stove. What does fit is the Sarle revenge theory, a recently fired geologist with the knowledge to fake caliche and the motive to humiliate the institution that had dismissed him, partnered with the man who would "discover" the results, but if the confession is not genuine, if Bessie wrote it herself for reasons we cannot know, then the mystery remains exactly where it was. As Don Burgess concluded, and I myself also conclude, these answers may never be found.

THOMAS BENT'S OBSESSION

Whatever the truth about the Tucson artifacts, whoever made them, whenever they were made, and for whatever reason, there is one thing that is not in dispute. Thomas Bent believed. He believed from the moment Charles Manier showed him the first cross in November 1924, and he never stopped. He filed a homestead claim on the discovery site, moved his family onto the property, and built a house near the old lime kiln. He spent years excavating, documenting, and defending the artifacts against an increasingly skeptical world. His notes on stratigraphy were better, by some accounts, than those of most professional archaeologists. He kept careful track of every object pulled from that hot Arizona ground.

(Artifact 24. Photo by Joseph Miele)

When the University of Arizona withdrew its $16,000 offer in January 1930, Bent took it as a betrayal. The institution that had promised to validate his discoveries had abandoned him, and the relationship never recovered. He refused to donate the artifacts to the university or to the Arizona State Museum. To Bent, the academics who dismissed the artifacts were elitist gatekeepers who lacked the courage to accept evidence that contradicted their assumptions. "I am firmer than ever in my belief that they are genuine," he wrote in response to hoax accusations. When confronted with the Timoteo Odohui theory, he retorted: "Where did this Mexican boy obtain his reported wonderful university education?"

Bent eventually produced a 350-page manuscript titled The Tucson Artifacts, a comprehensive defense of everything he had found and everything he believed. It was never published. It sits today in the archives readable only to researchers who are willing to take the trip to read them. It stands as a monument to one man's conviction.

Thomas Bent died in 1972 without vindication. The artifacts passed to his son, Thomas Bent Jr. and in 1994, the younger Bent finally donated the collection, not to the University of Arizona, but to the Arizona Historical Society. The artifacts were displayed briefly, then moved into the vault where they remain today, cataloged not as genuine relics of a lost civilization, but as curiosities from a century-old controversy. The current museum position on the artifacts, as relayed to me by Jace Dostal, is that they are a real and important piece of the history of Arizona, but that they do not have the age purported by the inscriptions.

If the Bessie Manier confession is true, then Thomas Bent was the person most deeply harmed by the hoax, not the University of Arizona, which recovered its reputation by distancing itself early, and not Byron Cummings, who moved on to other work. Thomas Bent gave decades of his life to defending objects that his own partner had possibly planted in the ground. He spent his family's money, staked his credibility, and fought the academic establishment on behalf of a possible lie he was never let in on, and he died a believer.

CONCLUSION

A century after Charles Manier pulled a sixty-five-pound lead cross from the desert hardpan along Silverbell Road, the Tucson artifacts remain in their vault at the Arizona Historical Society. They have outlasted everyone who found them, everyone who defended them, everyone who debunked them, and everyone suspected of creating them.

The forensic record is difficult to argue with. Many of the Latin inscriptions seem to be plagiarized from grammar textbooks available in 1920s Tucson. The Hebrew was assessed as nonsensical by scholars in 1925 and again decades later. Two separate metallurgical analyses, conducted generations apart using increasingly sophisticated technology, concluded that the lead is modern industrial material. A retired USGS geologist demonstrated that the caliche encasing the artifacts, the single most persuasive argument for their antiquity, could be manufactured in two days using materials available at the discovery site. The site itself produced no pottery, no glass, no bones, no tools, no housing remains, no evidence of human habitation of any kind.

(Artifact 13-1. Military Standard. Photo by Joseph Miele)

Certainty however, has its limits. We do not know, with finality, who made them. Timoteo Odohui had the skills and the location, but no obvious motive and no audience for his work. Clifton Sarle had the geological knowledge and a possible grudge against the university. Charles Manier had access and opportunity. The Bessie Manier confession names Sarle and Manier directly, describes methods consistent with the physical evidence, and offers an explanation for the mysterious "OL" inscription that only a forger would know. But the confession was written by Bessie herself, thirty-two years after her husband's death, and Alma Bent rejected it outright. Whether it represents the truth finally surfacing or an elderly widow's fabrication remains an open question.

We do not know the exact timing of the fabrication, or the full motive behind an effort that consumed over 150 pounds of lead, required inscriptions in two ancient languages, and produced thirty-two separate objects over what may have been years of work, all with no clear path to profit. We do not know whether Thomas Bent was a victim or something more complicated. We do not know why, if this was a collaborative effort, no one involved ever stepped forward during their lifetime to claim responsibility.

What we do know is that for a brief moment in the 1920s, some of the most respected scientific minds in the American Southwest looked at these objects and believed. Byron Cummings carried them across the country. The University of Arizona offered $16,000 to own them. Newspapers from Tucson to New York covered the story. It was the kind of discovery people wanted to be true.

That impulse, the desire for the extraordinary, the willingness to believe in something that reshapes what we think we know, is not a flaw. It is the same impulse that drives every legitimate archaeological excavation, every expedition into unmapped territory, every researcher who looks at the accepted narrative and wonders if something has been missed or lied about. The line between open-minded inquiry and wishful thinking is thinner than most people care to admit.

The artifacts still sit in their vault. The lime kiln ruins are still visible along Silverbell Road. The mystery endures, maybe not for what the artifacts might prove about ancient trans-Atlantic contact, but for what they reveal about the persistence of belief, the limits of evidence, and the human need to find meaning in what lies buried beneath our feet.

Notes and Sources

· Burgess, Don. "Romans in Tucson? The Story of an Archaeological Hoax." Journal of the Southwest, Vol. 51, No. 1 (Spring 2009), pp. 3-102.

· Bent Family Collection. Arizona Historical Society, Tucson, Arizona.

· Bent, Thomas W. "The Tucson Artifacts." Unpublished manuscript. Arizona State Museum, Tucson, Arizona.

· Arizona Daily Star and Tucson Citizen. Contemporary coverage, 1924-1930.

Acknowledgments

A special thank you to Jace Dostal, Statewide Collections Manager at the Arizona Historical Society and the Arizona History Museum, for granting after-hours access to examine and photograph the Tucson Artifacts firsthand. Their generosity and willingness to support independent research made this article possible.