The Tucson Silverbell Artifacts: Part 2 - The Evidence

ARGUMENTS FOR AUTHENTICITY

The Geological Evidence

The single most compelling argument for the artifacts' authenticity has always been where they were found. Every object came from a depth of four to six feet below the surface, embedded in a layer of hardened caliche, a calcium carbonate deposit that forms naturally in desert soils over long periods of time. The caliche around the artifacts had molded itself to their shapes, leaving clear impressions in the matrix.

Caliche formation is not a fast process. Under the natural, dry conditions in the Sonoran Desert, the building up of the kind of dense, cemented layer that encased these artifacts would take centuries. If the caliche formed naturally around the objects, then the objects had to have been in the ground for a very long time, far longer than the few decades separating the 1880s lime kiln operations from the 1924 discovery. This was the argument that convinced A.E. Douglass when he witnessed an extraction firsthand, and it was the argument that convinced Byron Cummings when he watched a sword blade pulled from solid caliche with a prospector's pick six days after returning from Mexico. Clifton Sarle, the geologist Bent and Manier brought onto the team, made the geological case his specialty. He argued that the caliche evidence alone proved the artifacts' antiquity and that no amount of human effort could replicate the natural cementation process in a short timeframe.

(A caliche berm in central Texas. Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.)

Expert Endorsement

The artifacts were not championed by amateurs alone. Byron Cummings, the dean of the University of Arizona's Archaeological Department and director of the Arizona State Museum, staked his professional reputation on their authenticity. A.E. Douglass, the founder of dendrochronology and one of the most methodical scientists in the Southwest, took the finds seriously enough to document them and correspond about them with colleagues. The University of Arizona itself invested time, personnel, and ultimately offered $16,000 to purchase the collection, a sum that reflected genuine institutional confidence, however short-lived the offer was. These were not fringe figures. They were among the most respected scientific minds in Arizona, and for a time, they believed in the authenticity and pre-Colombian age of the artifacts.

Scholarly Support

Academic interest in the artifacts did not end with the university's withdrawal in 1930. In 1975, Cyclone Covey, a classics professor at Wake Forest University, published Calalus: A Roman Jewish Colony in America from the Time of Charlemagne Through Alfred the Great, a book that can now pull in $500 in the used market, depending on its condition. Covey held a Ph.D. from Stanford, earned in 1949, and had taught at Reed College and Oklahoma State before joining the faculty at Wake Forest. He was not a crank. His book argued that the inscriptions were consistent with medieval Latin and Hebrew usage and that the Calalus narrative fit within a broader pattern of Rhadanite Jewish trade networks that spanned from Europe to Asia during the early medieval period. Covey took the artifacts seriously enough to plan excavations at the original site in 1972, but the University of Arizona blocked the effort.

More recently, Donald N. Yates, who holds a Ph.D. in Medieval Latin, published a photographic catalog of the artifacts with his complete transcriptions in 2017. Yates argues that the multi-script inscriptions reflect a sophisticated Roman-style military governorship, the kind of administrative apparatus that would naturally produce documents in multiple languages. His analysis treats the artifacts as a complete coherent archive rather than a collection of isolated fragments.

Multi-Script Writing

The artifacts bear inscriptions in both Latin and Hebrew. Proponents argue that this combination is itself evidence of authenticity. A forger working in 1920s Tucson would need competence in both ancient languages, not just vocabulary, but also the conventions of how each language was used in official and religious contexts during the early medieval period. Yates has argued that the presence of both scripts is consistent with how a Roman colonial administration with a significant Jewish population would have conducted its affairs, producing records in the administrative language of Rome alongside the liturgical language of its Jewish inhabitants.

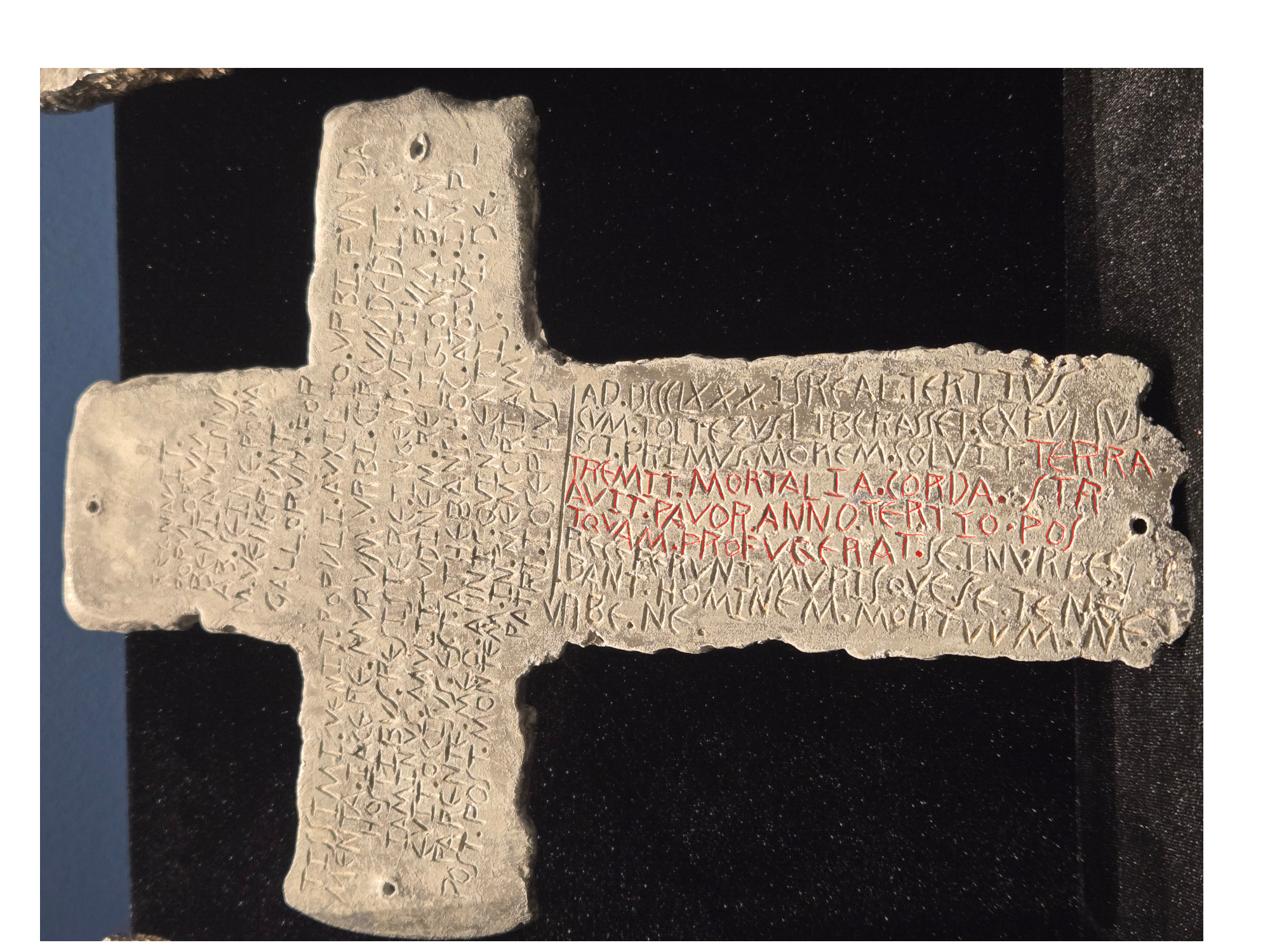

Item 3b, and part of 3a. Photo by Joseph Miele.

The Lost Wax Question

Donald Yates has put forward an argument about how the inscriptions were created. Rather than being engraved into the surface of the lead after casting, Yates contends that the lettering was formed through a lost wax process, a precision casting technique in which inscriptions are first carved into a wax model, which is then used to create a mold. Molten lead is then poured into the mold and the wax melts away, leaving the finished inscription. Yates points to the fluid quality of the letterforms as evidence, arguing that the characters show the kind of smooth, flowing lines that come from a stylus pressed into wax rather than a tool cutting into hardened metal. The lost wax technique itself dates to approximately 3000 BCE and requires significant metallurgical knowledge. Yates has described the craftsmanship as reflecting "secret arts not able to be duplicated or matched today."

Lead Provenance

Donald Yates claims that early testing by the Arizona Bureau of Mines examined the lead composition of the artifacts and found that it matched the output of the Old Yuma Mine, located roughly twelve miles from the discovery site. If Donald is correct, then the lead was local, not imported. Further analysis revealed that the artifacts were not uniform in composition. Different pieces contained varying amounts of antimony, tin, zinc, copper, gold, and silver. Proponents have argued that this variation is consistent with lead that was a byproduct of precious metal refining, the kind of material that would have been readily available to a settlement engaged in mining operations.

The Scale of the Effort

Across all thirty-two objects, the collection represents over 150 pounds of worked lead. Each piece required time and skill to create, casting or shaping the lead, inscribing text in two languages, and adding portraits, symbols, and decorative elements. For those who believe the artifacts are a hoax, this raises an uncomfortable question: why would someone invest this kind of effort with no clear path to profit? Bent and Manier never sold the artifacts. No one got rich. The $16,000 university offer was contingent on authenticity and was ultimately withdrawn. If this was a fraud, it was an extraordinarily labor-intensive one with no apparent payoff.

The Toltezus Reference

The inscriptions refer to the indigenous people the colonists encountered as the Toltezus. Proponents have noted that this appears to be a Latinization of the Nahuatl word Tōltēkah, or Toltecs, a real pre-Columbian Mesoamerican civilization. The argument is that this is too precise a detail for a forger to have invented. It’s a culturally specific reference that ties the Calalus narrative to actual indigenous history. The Toltecs were a powerful civilization whose influence shaped much of Mesoamerican culture and naming them as the adversaries of a colony in the Arizona desert suggests the artifact creator had knowledge of pre-Columbian peoples that went beyond casual familiarity.

Forensic Geology: The Wolter Investigation

In a more recent examination, forensic geologist Scott Wolter applied what he calls archaeopetrography, the application of geological analysis to archaeological questions, in order to determine whether the artifacts were planted or genuinely ancient. His investigation focused on three areas: mineral growth, local materials, and religious symbolism.

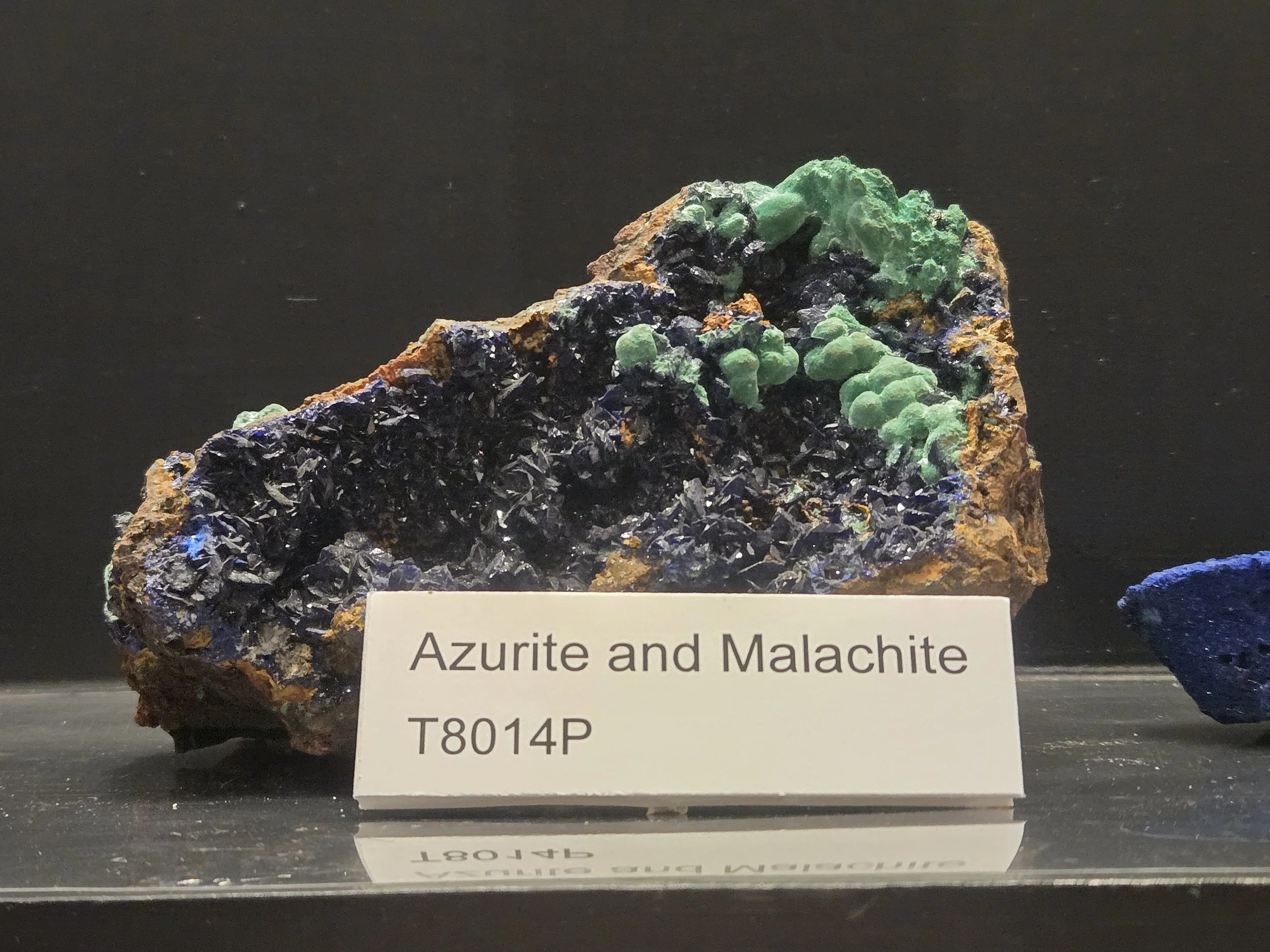

Using a 3D microscope, Wolter identified malachite and azurite crystals that had grown on the surfaces of the artifacts. Both are copper carbonate minerals that form through the slow weathering of copper in the presence of moisture and carbon dioxide. Wolter asserted that these crystals take hundreds of years to form underground and considered their presence a "smoking gun" for authenticity. He also confirmed that the caliche found on the artifacts matched the limestone source at the discovery site, consistent with the objects having been naturally encased over time. Wolter then visited the Old Yuma Mine and found ample lead ore, concluding that ancient explorers could have mined and manufactured the artifacts locally using simple manual labor.

On the question of symbolism, he identified a double-barred cross on the artifacts as the Cross of Lorraine, a patron symbol of the Knights Templar, and noted the presence of the square and compass as a possible link to ideologies that later formed Freemasonry. He dismissed the idea that the controversial engraving on one of the sword blades depicted a dinosaur, concluding instead that the image was a lizard with a forked tongue, consistent with the Arizona desert environment. His team also confirmed that the abbreviation "A.D." was in use by 800 AD, supporting the validity of the inscribed dates.

(The dinosaur on Artifact 94.26.12 s. IX. Photo by Joseph Miele)

Wolter's broader theory was that the artifacts were created by religious refugees from southern France, precursors to the Knights Templar, who fled Muslim persecution in the Mediterranean during the eighth or ninth century and traveled by ship to the American Southwest. He concluded with "absolute certainty" that the artifacts are legitimate pre-Columbian relics from the eighth to ninth century, a statement he framed as a vindication of Thomas Bent's lifelong belief.

ARGUMENTS FOR SKEPTICISM

The Latin Problem

If the geological evidence was the strongest argument for the artifacts' authenticity, the Latin inscriptions became the strongest argument against it. The problems began with the same man who had provided the first translations.

Professor Frank Fowler, head of the University of Arizona's Department of Classical Languages, had examined the first cross in 1924 and translated its inscriptions phrase by phrase. At the time, he noted that the text did not read as a coherent narrative, but he offered no definitive judgment on authenticity. Over the following years however, as more artifacts emerged and more inscriptions were transcribed, Fowler's position did an about-face. He reversed himself entirely, concluding that the Latin text was not the work of ancient scribes, but of someone with access to modern Latin textbooks.

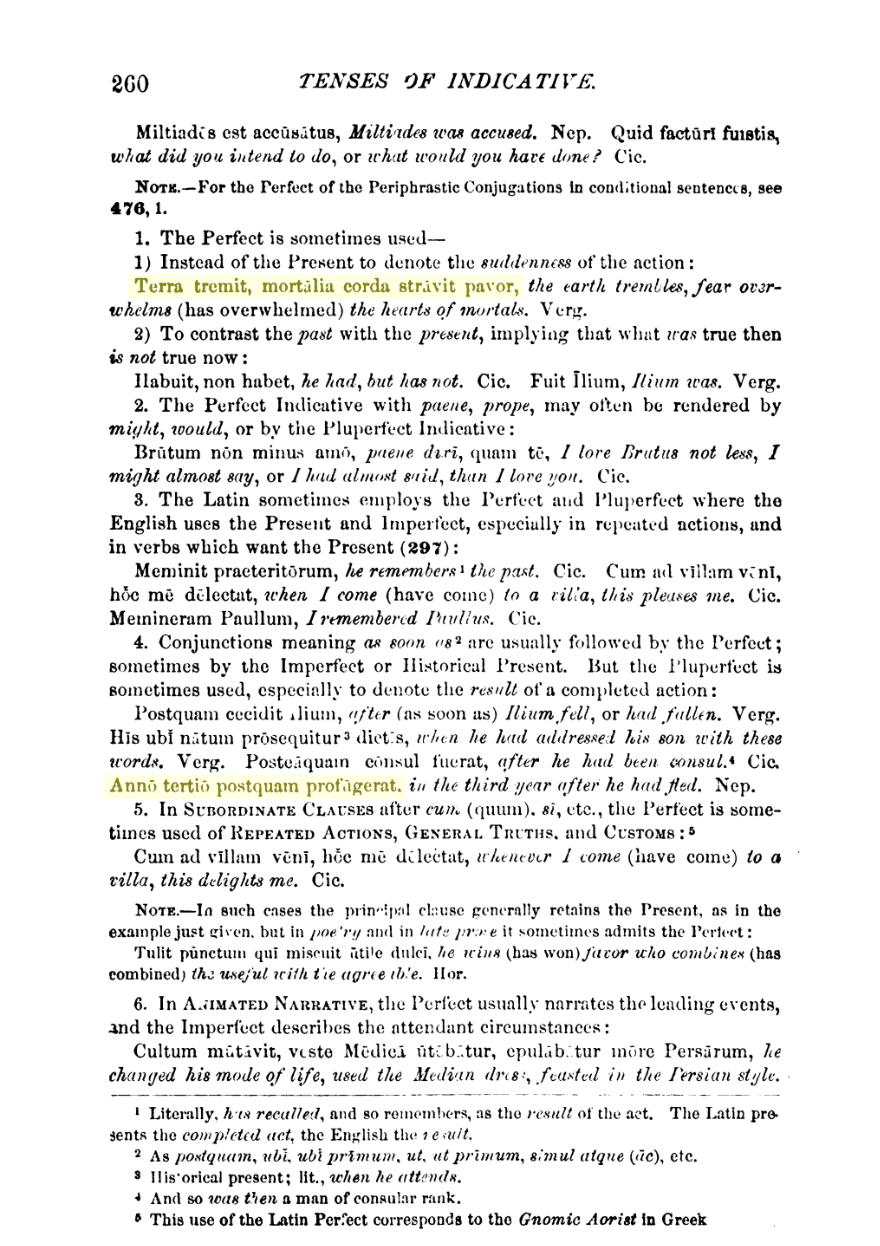

The reason was straightforward according to Professor Fowler: the inscriptions had been copied, in many cases word for word, from grammar exercises and example sentences found in standard Latin textbooks that were widely available in 1920s Tucson. Don Burgess, in his 2009 article "Romans in Tucson? The Story of an Archaeological Hoax" published in the Journal of the Southwest, documented the plagiarism. Phrases on the artifacts matched passages from Harkness's Latin Grammar (1881) and Allen and Greenough's New Latin Grammar (1903), both of which were used in Tucson-area high schools during the period when the artifacts were allegedly discovered. The source material wasn't obscure. It was excerpts of Cicero and Dante, chosen by textbook editors to illustrate grammatical rules. Fowler observed, "All this shows is that the compiler of these expressions was not telling a narrative."

(Artifact 5a. I have taken the liberty to outline in red the text that appears in the textbook A Latin Grammar for Schools and Colleges. Photo by Joseph Miele.)

(A Latin Grammar for Schools and Colleges, 1881, by Albert Harkness PhD. The text that appears on Artifact 5a has been highlighted.)

Beyond the apparent plagiarism, the Latin also contained anachronisms that pointed to modern composition. The phrase "Anno Domini" appears on several artifacts, and although that dating convention was in use before the eleventh century, it wasn’t widespread until then making it odd to see on a document dated from the 700’s, according to some scholars, which is of course debated by other scholars. Fun! The word "Gaul" appears where classical Latin would use "Gallia"; "Gaul" is an English word that entered the language around the 1560s. Additionally, the phrase post meridiem reflects modern phrasing rather than classical construction. Throughout the inscriptions, the grammar is inconsistent and frequently incorrect in ways that suggest the work is by a person working from reference materials rather than writing fluently in the language, but who said the maker of the artifacts had to be fluent?

The Hebrew Problem

The Hebrew inscriptions on the artifacts presented a different kind of problem: for decades, they were largely ignored. Despite appearing on multiple artifacts, the Hebrew text received remarkably little scrutiny during the initial controversy. No Hebrew scholars were brought in to examine the inscriptions during the 1920s excavations, or during the university's involvement. This was a significant oversight. The artifacts claimed to document a Jewish colony, bore Hebrew text alongside Latin, and yet the Hebrew went essentially unexamined while the debate focused almost entirely on the Latin and the geology.

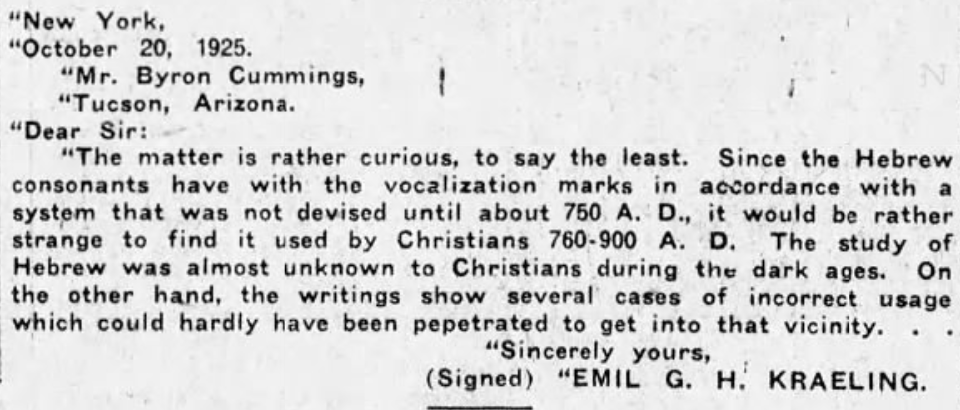

That gap was addressed, at least in part, long after the initial discovery. On October 20, 1925, Dr. Emil G.H. Kraeling, Professor of Oriental Language at the Union Theological Seminary in New York City, wrote directly to Byron Cummings with his assessment. Kraeling noted that the Hebrew consonants on the artifacts included vocalization marks "in accordance with a system that was not devised until about 750 A.D," making it "rather strange to find it used by Christians 760-900 A.D." He pointed out that "the study of Hebrew was almost unknown to Christians during the dark ages." Kraeling also found that "the writings show several cases of incorrect usage which could hardly have been perpetrated to get into that vicinity," meaning, the errors were not the kind that would result from centuries of linguistic evolution. They were the kind made by someone unfamiliar with the language.

Letter from Emil G.H. Kraeling to Byron Cummings, courtesy Arizona Daily Star, Dec. 13, 1925

Donald Yates, the most prominent modern defender of the artifacts, has argued that the Hebrew reflects sophisticated Masoretic conventions, suggesting the work of educated Jewish scribes, but a thesis by Paul Thomas, written while a student at the University of Kansas, a copy of which I was made privy to at the Arizona History Museum, examined the Hebrew inscriptions and reached a very different conclusion. The Hebrew, according to the thesis was rudimentary, without meaningful context, and it did not reflect the work of literate Hebrew speakers. So, if portions of the Latin were plagiarized from textbooks and the Hebrew seemed to not tell much of a story at all, then the two languages that were supposed to authenticate the artifacts as the records of a Roman-Jewish colony were going to fall short, for many.

Metallurgical Analysis: Chapman, 1929

The inscriptions were not the only evidence subjected to scientific testing. In 1929, Thomas G. Chapman, head of the University of Arizona's Department of Mining Engineering and Metallurgy, analyzed a sample from one of the artifacts. Chapman held a Doctor of Science degree from MIT and would go on to become dean of the university's Graduate College. He was a credentialed expert in extractive metallurgy.

According to Dr. Chapman, the lead was not raw or crudely smelted ore of the kind one might expect from an eighth-century frontier colony. It was a synthetic lead-antimony alloy known by the trade name "type metal," the same material used in nineteenth and twentieth century printing presses to cast movable typefaces. The antimony added toughness to the soft lead, and traces of tin improved fluidity for pouring into molds. Chapman's conclusion was that the material had been "produced in comparatively recent times."

Metallurgical Analysis: Killick and Thomas

David Killick and Noah Thomas, both affiliated with the University of Arizona, contributed to Don Burgess's 2009 investigation by providing an analysis of the lead composition of the artifacts. Their work employed lead isotope analysis, a technique far more sophisticated than Chapman's 1929 assay, capable of identifying not just what the lead was made of, but where it had come from. Their findings confirmed and extended Chapman's conclusions. The lead in the artifacts carried isotopic signatures consistent with post-nineteenth-century industrial scrap, including battery remnants and printing material waste.

(Artifact 3a, and part of 3b. Photo by Joseph Miele)

The Quinlan Experiment

The geological argument, that caliche takes centuries to form and therefore the artifacts must be ancient, had been the bedrock of the authenticity case since Cummings first watched a sword blade pulled from cemented soil. In 2000, retired USGS geologist James Quinlan decided he was going to take a stab at it. Quinlan bought quicklime from a store, mixed it with sand and gravel, inserted a lead rod into the mixture, and waited. Within two days, the mixture had hardened into material that was visually indistinguishable from natural caliche. The lead rod was firmly encased, and the artificial deposit looked and felt like something that had been forming in the desert for centuries.

The artifacts had been found at a lime kiln, a site whose entire purpose was the production of quicklime, therefore calcium oxide, water, sand, and gravel were not exotic materials that would need to be sourced from elsewhere; they were the raw materials of the kiln's daily operations. Anyone with access to the site could have mixed artificial caliche, buried lead objects in it, and returned months or years later to "discover" them embedded in what appeared to be an ancient geological formation. The cemented caliche that had convinced Douglass, Cummings, and Sarle that the artifacts were genuinely old could have not only been feasibly, but easily manufactured on-site, and in a matter of days.

Physical Evidence of Modern Fabrication

Beyond the chemistry of the lead and the composition of the surrounding soil, the artifacts themselves showed possible signs of modern tooling. Artifact 14, a spear point, bears possible file marks visible on its surface. Artifact 15, a sword blade, shows possible evidence of hammer and vice marks, the kind of impressions left by tools used to shape metal in a modern workshop, not by artisans working with ancient casting techniques. These aren’t the things one expects to find on objects supposedly created through a lost wax process over a thousand years ago.

(Artifact 14 with possible file marks. Photo by Joseph Miele.)

(Artifacts 15 showing possible modern hammer marks. Photo by Joseph Miele.)

The surface condition of the artifacts raised additional questions. Some artifacts showed fresh scratches in locations consistent with being inserted into pre-dug holes rather than having been slowly encased by natural geological processes. And then there was the problem that had helped push the University of Arizona toward its 1930 withdrawal: one artifact was physically shorter than the hole it had allegedly been found in. If the caliche had formed naturally around the object over hundreds of years, the impression in the soil should match the object's dimensions exactly. A hole larger than the artifact it contained suggested the hole came first and the artifact was placed into it afterward.

The Absence

Perhaps the most telling evidence against the artifacts is not what was found at the site, but what wasn't. The Calalus inscriptions describe a colony of Roman-Jewish settlers who lived in the Arizona desert for 125 years, fought prolonged wars, built a fortified city, and maintained a population large enough to field armies for prolonged battles. A settlement of that scale and duration would leave an enormous archaeological footprint. There should be pottery. There should be glass fragments, animal bones, hearths, housing foundations, trash middens, tools, human remains, and the diverse assemblage of debris that accumulates through normal human activity over more than a century of habitation. Hundreds of people living, cooking, fighting, building, and dying in one place for 125 years would leave evidence that no amount of time could erase entirely. The site produced none of it. No pottery sherds. No glass. No bones. No structural remains. No tools. No evidence of human habitation of any kind beyond the lead artifacts themselves. The only things found at the lime kiln site were the things that told the Calalus story. Everything that would corroborate that story, the material evidence of actual human life, was absent.

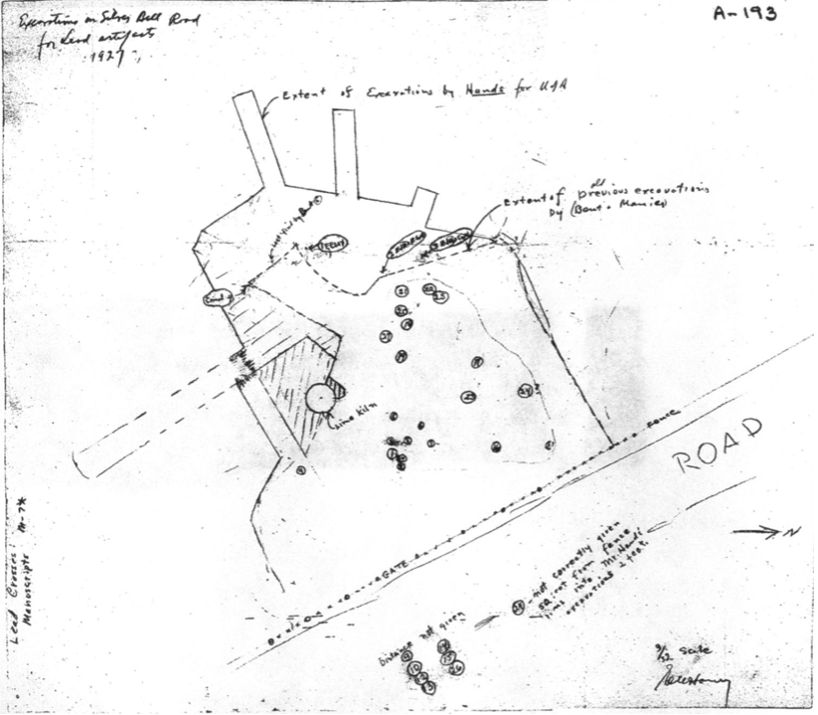

(Map of the Silverbell site drawn by Emil Haury in 1927. Photo courtesy of Arizona State Museum Archives.)

The Anachronisms

Several details on the artifacts are difficult to reconcile with an eighth- or ninth-century origin. One sword blade bears an engraving that appears to depict a dinosaur, an animal whose existence was unknown until nineteenth-century fossil discoveries. Knowledge of what we believe dinosaurs looked like was not available to anyone living in 800 AD. Defenders have argued that the image represents ancient knowledge of prehistoric creatures, or alternatively that it depicts a lizard or dragon rather than a dinosaur. Critics see it as evidence that the engraver lived in an era when dinosaurs were part of popular culture.

The artifacts also display an eclectic combination of religious and cultural symbols that would be historically unusual for any single community in the early medieval period. Roman imagery, Jewish symbols including menorahs and Hebrew inscriptions, Christian crosses and angels, and Masonic symbols including a square and compass on Artifact 20, all appear across the collection. While individual elements might plausibly appear in a multicultural colonial context, to me at least, the specific combination reads less like the organic output of a real community and more like the work of someone attempting to include every ancient and mysterious symbol they could think of.

(Artifact catalog 94.26.20 Reverse Side. Nehushtan. The front of this artifact contains 2 squares and compasses along the flanges of the crescent. These can. be seen in person, or in Don Burgess report. Photo by Joseph Miele)

The Malachite Question

Scott Wolter's identification of malachite and azurite crystals on the artifacts, and his assertion that they represent a "smoking gun" for authenticity, in my opinion, warrants a little scrutiny. Wolter claimed that these copper carbonate minerals take hundreds of years to form underground, and therefore their presence on the artifacts proves that they are ancient. I believe the science is a bit more nuanced.

Malachite and azurite form when copper ions react with carbon dioxide and water. The rate at which this occurs depends heavily on local conditions, ie. moisture levels, temperature, pH, and importantly the availability of copper and carbonate ions in the surrounding environment. Arizona is one of the most copper-rich regions in the United States, with extensive and verifiable mining operations dating back well into the nineteenth century, and possibly even before the historical era. Copper-bearing groundwater is common throughout Arizona and is found locally in the region.

The discovery site itself may have provided unusually favorable conditions for exactly this kind of mineral growth. Lime kilns operate by burning limestone, calcium carbonate, at high temperatures to produce quicklime, or calcium oxide. The process drives off carbon dioxide and breaks the carbonate apart. Quicklime is chemically reactive, however. When exposed to water, it becomes slaked lime, and when slaked lime is exposed to carbon dioxide in the air or in groundwater, it re-carbonates, converting back into calcium carbonate. An old lime kiln site, after decades of operations, spillage, and waste accumulation, would leave the surrounding soil rich in calcium carbonate. Not only that, but we’re also talking about artifacts that were encased in caliche, which is itself calcium carbonate. Combine that carbonate-rich environment with the copper ions common in Arizona groundwater, and you have the two essential ingredients for malachite and azurite formation: copper and carbonate, together in the same soil, reacting in the presence of moisture. Remember, the discovery site is alongside the west bank of the Santa Cruz River. In other words, the lime kiln site is not just a location where artificial caliche could be manufactured in days, it is also an environment where copper carbonate minerals could form on buried metal objects at an accelerated rate.

On exposed copper surfaces, visible green patina, which includes malachite, can begin developing within years and mature substantially within five to twenty years. The Statue of Liberty comes to mind. Underground conditions vary, but it seems there is no firm minimum of "hundreds of years" for microscopic crystal formation on buried metal objects. The growth rate is dependent more on conditions, and less on a fixed geological clock. At a lime kiln site in the copper mining heartland of Arizona, those conditions would have been exceptionally favorable.

Azurite and Malichite, sourced from Southern Arizona. Photo by Joseph Miele.

Notes and Sources

· Burgess, Don. "Romans in Tucson? The Story of an Archaeological Hoax." Journal of the Southwest, Vol. 51, No. 1 (Spring 2009), pp. 3-102.

· Covey, Cyclone. Calalus: A Roman Jewish Colony in America from the Time of Charlemagne Through Alfred the Great. New York: Vantage Press, 1975.

· Yates, Donald N. The Tucson Artifacts: An Album of Photography with Transcriptions and Translations of the Medieval Latin. 2017.

· Chapman, Thomas G. Metallurgical assay of the Tucson Artifacts, 1929. University of Arizona Department of Mining Engineering and Metallurgy.

· Killick, David, and Noah Thomas. Lead isotope analysis of the Tucson Artifacts. University of Arizona.

· Quinlan, James. Caliche formation experiment, 2000. Findings shared with Don Burgess.

· Kraeling, Emil G.H. Letter to Byron Cummings regarding the Hebrew inscriptions, October 20, 1925. Published in the Arizona Daily Star, December 13, 1925.

· Fowler, Frank H. Translation of artifact inscriptions. Arizona Daily Star, 1924-1925.

· Thomas, Paul. Thesis on the Hebrew inscriptions of the Tucson Artifacts. University of Kansas. Copy held at the Arizona Historical Society, Tucson, Arizona.

· Allen, Joseph Henry, and James Bradstreet Greenough. Allen and Greenough's New Latin Grammar. 1903.

· Gildersleeve, Basil Lanneau. Gildersleeve's Latin Grammar.

· Harkness, Albert. Harkness's Latin Grammar. 1881.

· "The Desert Cross." America Unearthed, Season 1, Episode 1. H2 (History Channel), 2013.

Acknowledgments

A special thank you to Jace Dostal, Statewide Collections Manager at the Arizona Historical Society and the Arizona History Museum, for granting after-hours access to examine and photograph the Tucson Artifacts firsthand. Their generosity and willingness to support independent research made this article possible.