The Tucson Silverbell Artifacts: Part 1 - The Discovery

INTRODUCTION

On September 13, 1924, Charles Manier and his family stopped to explore an abandoned lime kiln along Silverbell Road, northwest of Tucson, Arizona. While poking around the weathered structure, Manier noticed something protruding from the hardened caliche soil. He pulled at it, dug around it, and finally freed a massive lead cross weighing over sixty pounds. What seemed like a curious roadside find would become one of the most debated archaeological discoveries in Arizona history.

(Tucson in the early 1900’s. Photo courtesy of Library of Congress.)

Over the next six years, thirty-one lead objects emerged from that site. There were crosses, swords, spearheads, Nehushtans, most of them bearing elaborate inscriptions in Latin and Hebrew, alongside etched symbols representing a myriad of religions and mystery traditions. The artifacts told a remarkable story: a Roman-Jewish colony called "Calalus" existed in Arizona from 775 to 900 AD. The kings mentioned on the artifacts were named Theodore, Jacob, and Israel. They fought prolonged wars with the Toltezus people, captured hundreds of prisoners (or had hundreds of their own captured), endured civil conflicts and earthquakes, and left behind a detailed chronicle carved in lead.

The discovery captured national attention. The University of Arizona offered $16,000 to purchase them, with the stipulation that they were only obligated to pay if the artifacts were found to be genuine. Byron Cummings, director of the Arizona State Museum, took ten artifacts on tour to the American Association for the Advancement of Science, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and the Smithsonian. The New York Times ran many features about the artifacts. Experts examined them, debated them, and took sides.

(The University of Arizona in 1909. Photo courtesy of Library of Congress.)

Some scholars staked their reputations on the artifacts' authenticity, stating that the geological context, the craftsmanship and the weight of evidence suggested something genuinely ancient. Others identified problems relatively quickly, inscriptions that matched Latin textbooks, metallurgy that pointed to modern fabrication, and a complete absence of supporting archaeological evidence and context.

A century later, the debate continues. Researchers like Donald Yates argue the artifacts represent genuine pre-Columbian contact. Others point to a 1973 confession letter suggesting the discoverers themselves created them. The evidence is complex, contradictory, compelling from multiple angles and makes for quite the mind-bender to organize, straighten-out and write about. So, strap in. It’s going to be a bumpy ride.

Who made these artifacts? When were they created? Was this an elaborate prank that spiraled out of control? Was it a sincere attempt to rewrite history? Or could they actually be what they claim to be?

The Collections Manager at the Arizona History Museum, Jace Dostal, was kind enough to open the museum to me on an off day in order to open the vault and give me firsthand access to these artifacts. I was able to photograph them, film them and pick his brain along the way.

This is the story of the Tucson Artifacts.

THE DISCOVERY

September 13, 1924

Charles Manier, his wife Bessie, their daughter Ethel, and Charles's father J.E. Manier were driving home one day from a day trip to the Picture Rocks area west of Tucson. The Arizona heat was as unforgiving as always. As they made their way back along Silverbell Road, they passed an abandoned lime kiln, one of several scattered across the desert landscape. Something about the old structure caught their attention and since they were ready to take a break from the driving, they pulled over to take a look.

While exploring the weathered ruins, Charles noticed something unusual protruding about two inches from the caliche-hardened ground near the kiln. He dug around it and worked the compacted soil loose. When it finally came free, he found himself holding something unexpectedly heavy, a lead cross measuring roughly twenty inches across and weighing almost sixty-five pounds.

The First Cross

Manier carried the artifact to the car, enraptured by what he'd found. Once home, he began the work of cleaning decades of dirt and oxidation from the artifact. As the grime fell away, he realized he was looking at something far more complex than a simple cross.

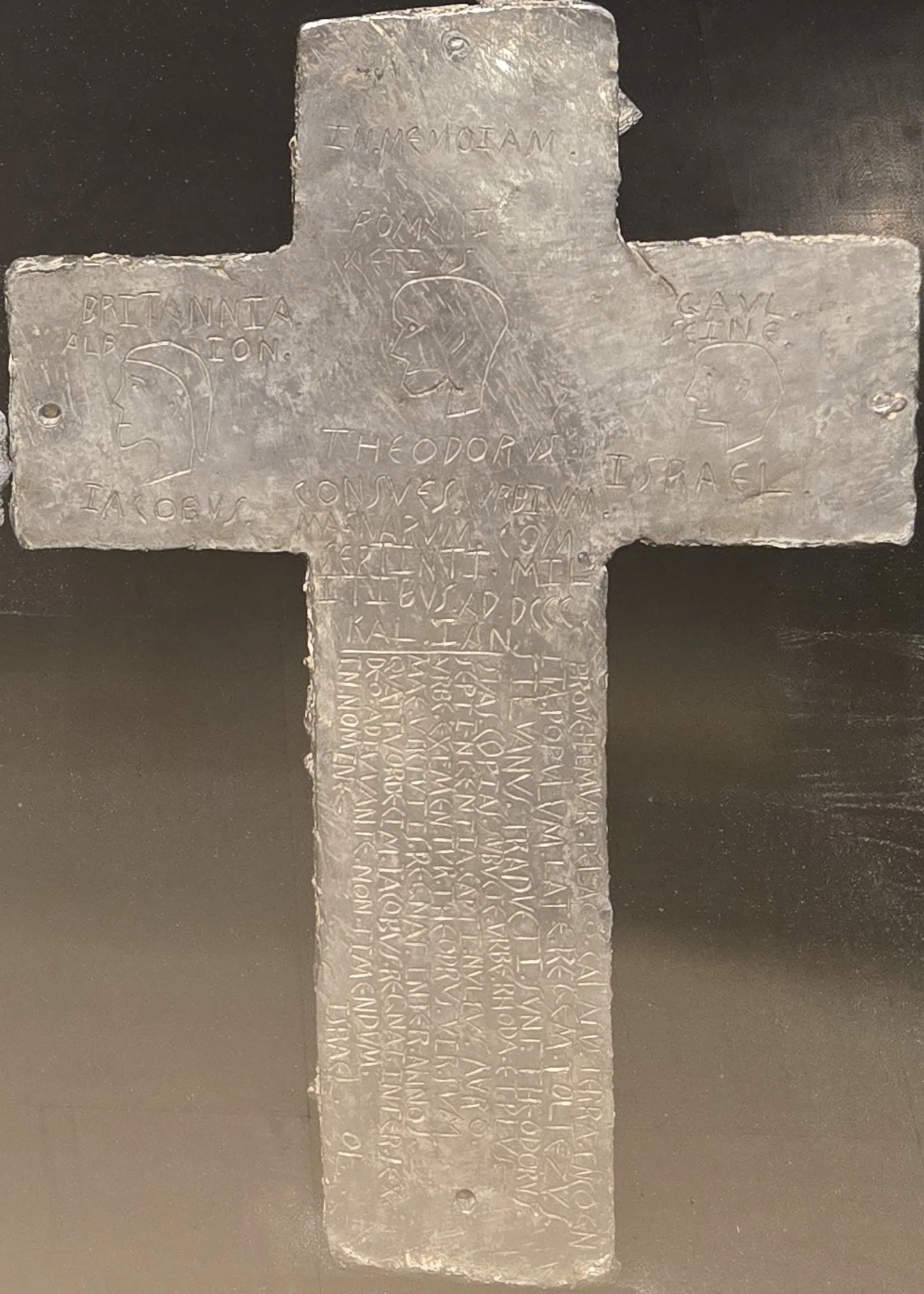

The object was actually two separate crosses, riveted together face-to-face. Between the smooth outer surfaces, a thick layer of waxy substance had formed a protective seal. Manier carefully pried the halves apart. The waxy substance had preserved the inner surfaces remarkably well, and those inner surfaces were covered in engravings.

Latin text ran down the center of the cross. Three faces appeared in profile across the arms, each labeled with a name: IACOBVS, THEODORVS, ISRAEL. Above each face respectively were the words: BRITANNIA ALBION, ROMANI AETIUS and GAUL SEINE. Someone had gone to considerable effort to create something elaborate. However, since the text was in Latin, Manier couldn't read it.

(Artifact 1a. Photo by Joseph Miele.)

Mrs. Kinnison and the University

By fortunate coincidence, one of the Manier family’s neighbors was a Mrs. A.F. Kinnison. When she saw the inscriptions, she immediately recognized them as Latin. By way of her husband, he a professor at the University of Arizona, she knew Professor Frank H. Fowler, who headed the university’s Department of Classical Languages. Mrs. Kinnison directed Manier to contact Professor Fowler.

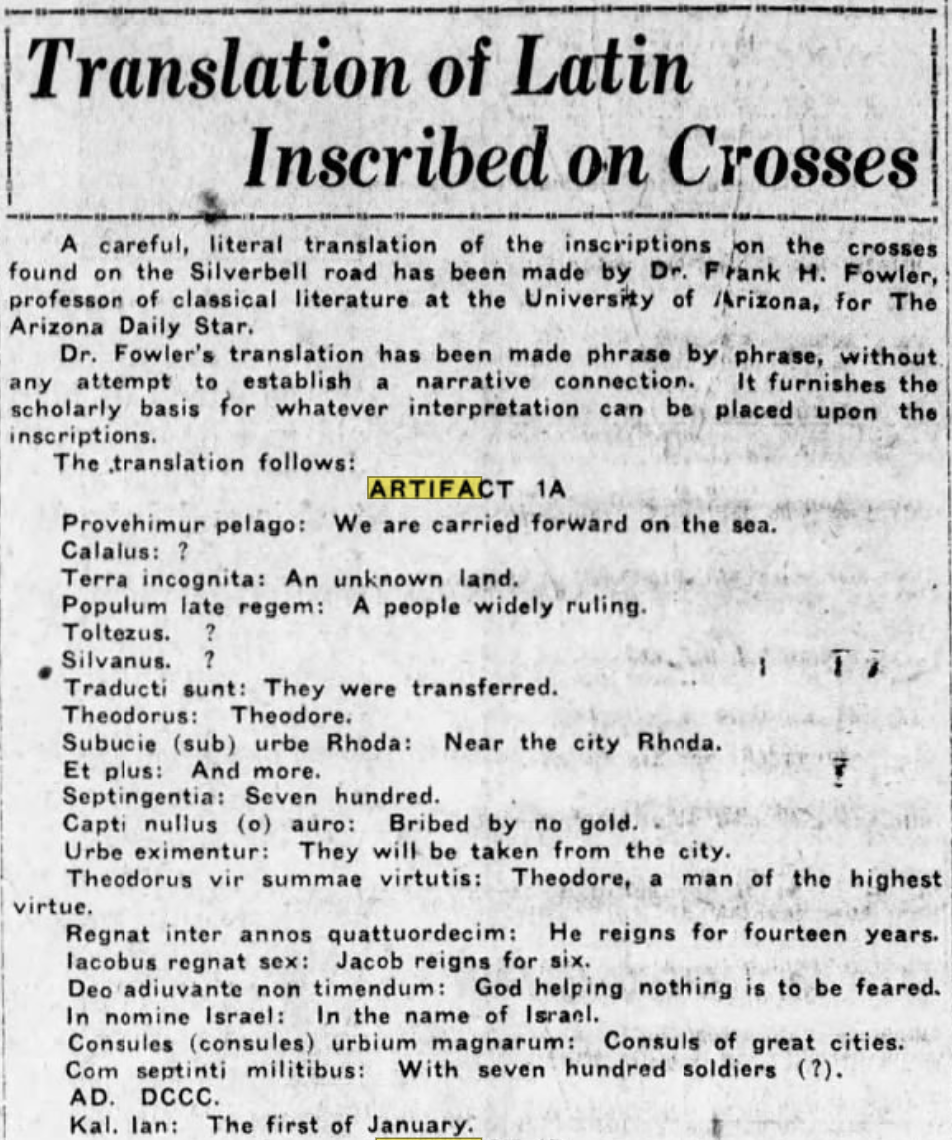

Fowler examined the artifact with interest and translated the text on the face of the cross now labeled 1A. He did this he said, phrase by phrase, without attempting to create a narrative:

ARTIFACT 1A

Provehimur pelago: We are carried forward on the sea.

Calalus: ?

Terra incognita: An unknown land.

Populum late regem: A people widely ruling.

Toltezus. ?

Silvanus. ?

Traducti sunt: They were transferred.

Theodorus: Theodore.

Suburis (sub) urbe Rhoda: Near the city Rhoda.

Et plus: And more.

Septingentia: Seven hundred.

Capti nullus (e) auro: Bribed by no gold.

Urbe eximentur: They will be taken from the city.

Theodorus vir summas virtutis: Theodore, a man of the highest virtue.

Regnat inter annos quattuordecim: He reigns for fourteen years.

Israel regnat sex: Jacob reigns for six.

Deo adiuvante non timendum: God helping nothing is to be feared.

In nomine Israel: In the name of Israel.

Consules (consules) urbium magnarum: Consuls of great cities.

Com septinti militibus: With seven hundred soldiers (?).

AD. DCCC.

Kal. Ian: The first of January.

The cross bore Roman numerals that, when interpreted as a date, indicated 800 AD. Whatever Manier had found, it appeared to be very old. He realized he might have stumbled onto something extraordinary, but he had no idea that this single find would multiply into thirty-two total objects and launch a controversy that would divide experts for the next century.

For now, the question for Charles was simple: What else was buried at that old lime kiln?

(Professor Fowler’s transcription of item 1a. Courtesy of the Arizona Daily Star, Sun Dec. 13, 1925.)

THE EXCAVATION BEGINS (1924 – 1930)

In November 1924, Charles Manier brought his friend Thomas Bent to the old lime kiln. Bent was a self-schooled lawyer who passed the bar without a high school education, a go-getter if there ever was one. He was also a businessman, and importantly, someone who shared Manier's excitement about the discovery. When Bent examined the first cross and heard Manier's telling of how he found it, he agreed to return to the site immediately.

It didn't take long before they found more artifacts. One by one more lead objects were unearthed from the hardened caliche, similarly encrusted and engraved. There were found additional crosses, swords, and spearheads. They must have been thinking that if there were more artifacts buried here, someone needed to secure the site and excavate it properly.

(Figure 1. Charles Manier with one of the lead swords. Courtesy of University of Arizona Library, Special Collections, A.E. Douglass Collection, Box 47, Folder 9.)

Bent investigated the land's ownership status and discovered the property was unowned. He immediately filed to homestead it, claiming the site as his own. Within months, Bent moved his family onto the property and built a house near the old lime kiln. The partnership between Manier and Bent was now official, and they began a systematic excavation of the site.

Bent and Manier soon brought in Clifton Sarle, a geologist who had been let go from his position at the University of Arizona three years previous for “not being well suited to teaching,” while at the same time being lauded by his former employer as an “excellent field geologist.” Sarle examined the site and the caliche formations and became convinced of the artifacts' authenticity. His geological expertise lent early credibility to the discoveries, particularly his assessment that the caliche layer would have taken centuries to form naturally around the objects. Now that Sarle was on the team and he was contracted to receive his 5 percent, it was now his job to write press releases and other promotional materials that would support the artifacts’ authenticity while Bent and Manier did the lions share of the digging.

(Clifton J. Sarle. Courtesy of Arizona Historical Society. Portrait 50030.)

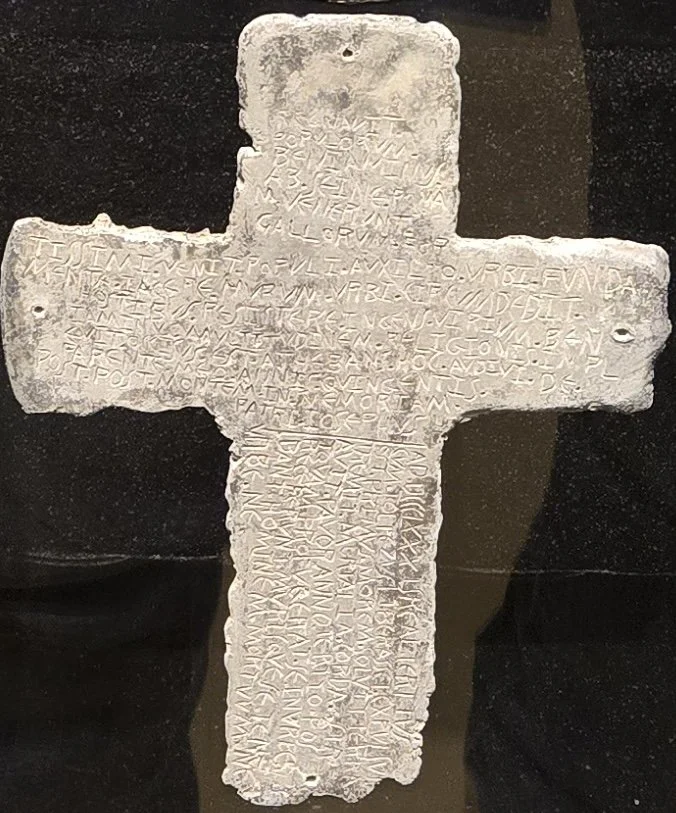

Over the next six years, the artifacts kept coming. Each discovery seemed to add another piece to a larger puzzle. By the time the excavations ended in 1930, the collection had grown to thirty-two separate objects: including lead crosses (six of them paired and riveted together like the first discovery), lead swords and sword fragments, lead spearheads and spear shafts, lead ceremonial standards, lead Nehushtans (which are crosses with serpents intertwined on them) and one caliche plaque bearing inscriptions with a simple human figure in profile.

Combined, the artifacts represented over 150 pounds of lead. This was a substantial amount of worked metal, each piece requiring time, skill, and effort to create. Every artifact came from the same depth, four to six feet below the surface, embedded in the caliche layer. The caliche itself left clear impressions around many of the objects, as if they had been buried for so long that the soil had molded itself around their shapes over the centuries.

(Artifact site. Courtesy of University of Arizona Library Special Collections, A. E. Douglass Collection, Box 147, Folder 9)

The newly discovered crosses also had Latin, as well as Hebrew writing around them, but neither Manier nor Bent could read it. Besides Professor Fowler, a high school history teacher in Tucson who had studied Latin named Laura Coleman Ostrander, began to work with the team. Ostrander took on the painstaking task of transcribing every inscription, translating what she could, and creating detailed sketches of each artifact. It was slow, meticulous work that took months to complete. Some inscriptions were clear and well-preserved, while others were fragmentary, worn, or difficult to read.

What emerged from Ostrander's translations was a story unlike anything found in the archaeological record of the American Southwest. She pieced together a narrative of what appeared to be a Roman-Jewish kingdom in the desert, which the inscriptions called Calalus. The artifacts described a dynasty of kings, including Theodorus, Jacobus, Israel the First, and Israel the Second, with inscriptions linking them to places like Britannia, Albion, Gaul, and the Seine. The colonists had been carried over the sea to this new land, where they founded a city called Rhoda, possibly located at what is now Tumamoc Hill west of downtown Tucson.

The colonists weren't alone, however. They encountered a people the inscriptions called the Toltezus, and what followed was a prolonged and brutal conflict. The artifacts documented a 125-year war between the colonists and the indigenous population, a struggle that presumably claimed thousands of lives on both sides. The inscriptions recorded the capture of over 700 prisoners (it is unclear who captured who), wars that killed thousands of people, and leadership that passed through multiple kings.

The dates inscribed on the artifacts ranged from 790 AD to 900 AD, spanning more than a century of recorded history. Artifact 5 mentioned a devastating earthquake in 895 AD. What appears to be the final inscriptions suggested the colony's end came around 900 AD, though the artifacts offered no clear explanation for what happened to the survivors or why the settlement was abandoned.

(Artifact 5. Photo by Joseph Miele)

It was an extraordinary narrative, a lost Roman-Jewish colony in pre-Columbian America, complete with dates, names, battles, and a detailed chronicle of survival and conflict in a hostile land. If the artifacts were genuine, they would rewrite everything historians thought they knew about trans-Atlantic contact before Columbus, and, if they were genuine, they were worth far more than the homesteaded plot of land where they'd been found.

UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA INVOLVEMENT

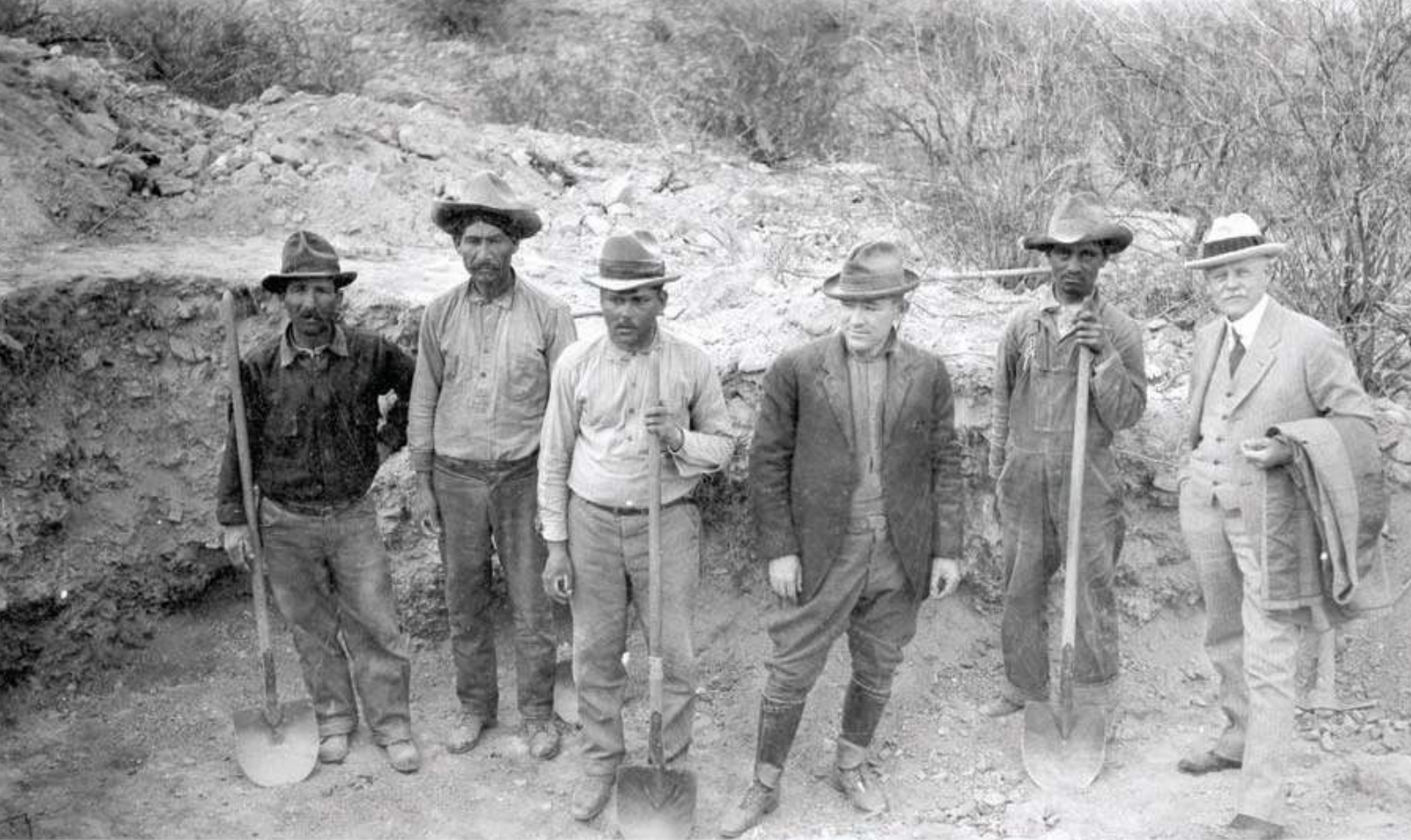

The artifacts didn't stay secret for long. Word spread through Tucson about the extraordinary discoveries at the old lime kiln, and by late 1924, they had caught the attention of faculty at the University of Arizona. The timing, however, was complicated. Dr. Byron Cummings, the dean of the Archaeological Department and director of the Arizona State Museum, was away excavating the ancient site of Cuicuilco in Mexico when the first of the Tucson artifacts was discovered in September 1924. In his absence, his colleagues Karl Ruppert and A.E. Douglass handled the university's informal examination of the finds.

Douglass was a respected scientist, the pioneering founder of dendrochronology, the science of tree-ring dating. His initial reaction to the artifacts was skeptical, and I remember seeing it mentioned that he thought it was a joke, but that skepticism wavered when he witnessed an excavation and saw objects being removed from what appeared to be undisturbed caliche. On March 14, 1925, Douglass wrote to Cummings in Mexico describing how Charles Manier and Thomas Bent kept bringing in "lead crosses and weapons" from the site. The cemented material had piqued his interest, even if he remained uncertain about what to make of the discoveries.

(A.E. Douglass. Photo courtesy Arizona Historical Society. Tucson. Portrait 13858)

When Cummings returned to Tucson around September 12, 1925, Douglass was reportedly relieved to turn the, what was becoming a ‘problem,’ over to him. Cummings was not just any archaeologist. He was one of the most respected figures in Southwestern archaeology, a man whose professional judgment carried enormous weight, and he wasted no time getting involved. On September 18, 1925, just six days after his return, Cummings personally witnessed the removal of a sword blade from solid caliche. The excavation required a prospector's pick to break through the hardened material, and the difficulty of the extraction helped convince Cummings that the artifacts were coming from genuinely undisturbed deposits. By December 1925, Cummings had become the primary scientific authority defending the artifacts. He issued public statements declaring the relics "without question, authentic" and argued they had existed hundreds of years before Spanish conquistadors entered the Southwest.

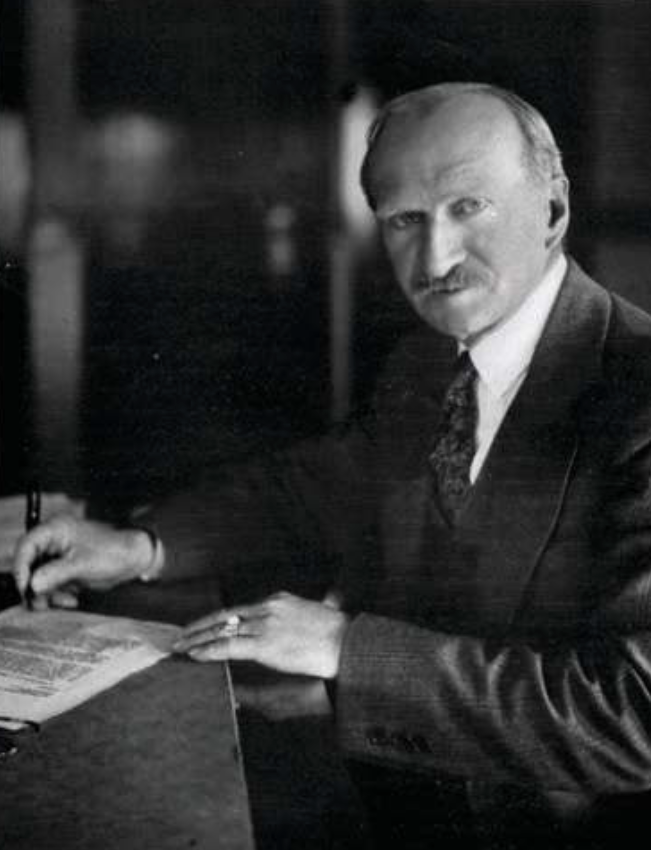

(Byron Cummings in 1927 while President of the University of Arizona. Courtesy of Arizona Historical Society, Tucson, Portrait File 42568 11831)

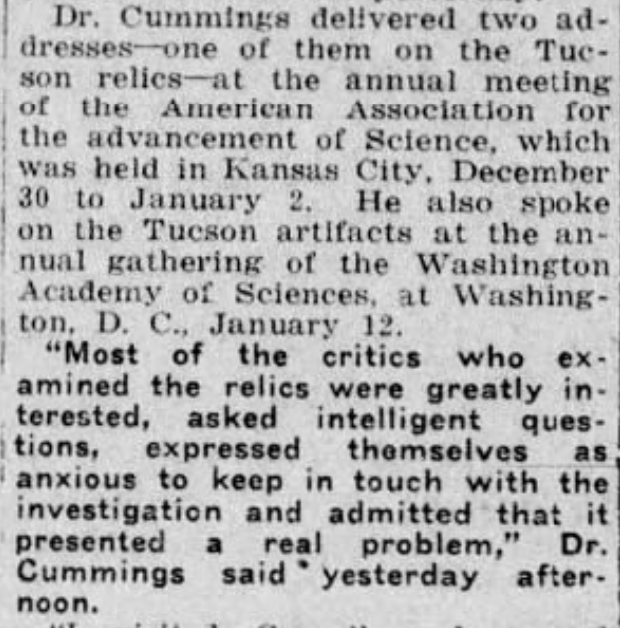

Cummings didn't stop at public statements, however. Convinced he was holding evidence of pre-Columbian trans-Atlantic contact; he selected ten of the most impressive pieces and embarked on what amounted to a three-week campaign to win over the national archaeological establishment. In late December 1925, he brought the artifacts to the annual meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science in Kansas City, where he delivered two addresses presenting the finds to his colleagues. From there he continued east, determined to show the relics to what he called "cynical colleagues and eastern archaeological authorities."

(Arizona Daily Star. Jan. 19, 1926.)

The tour took him to Washington, D.C., where he presented the artifacts before a group of scientists, and then to Princeton and Cornell Universities, where he consulted with additional experts. Finally, he returned to Tucson on January 17, 1926, after three grueling weeks on the road. For Bent and Manier, Cummings's willingness to personally carry their artifacts across the country and present them to some of the most prestigious institutions in America must have felt like vindication. If the dean of University of Arizona’s Archaeological Department was staking his reputation on these objects, how could they be anything but genuine?

The eastern reception was far from unanimous, however. Bashford Dean, the influential curator at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, examined the artifacts and remained unconvinced. George Vaillant at Harvard and F.W. Hodge at the Southwest Museum expressed similar reservations. It seemed that not all the experts Cummings had hoped to convert were so easily persuaded. Still, the tour generated enormous publicity. It did find experts in support of the artifacts too, and Cummings returned to Tucson with his confidence apparently unshaken.

In January 1928, the University of Arizona formalized its interest with an extraordinary offer. The university agreed to pay Bent and Manier $16,000 for the entire collection, contingent on the artifacts proving to be genuinely pre-Columbian. It was an enormous sum for 1928, equivalent to well over $200,000 today. For Bent, who had invested years of his life and moved his entire family onto the site, the offer must have seemed like a just reward for his hard work. The university's willingness to pay such a price suggested they took the artifacts seriously.

(Courtesy of University of Arizona Library Special Collections, A. E. Douglass Collection, Box 147, Folder 9 A.E. Douglas is on the right. Charles Manier is third from right.)

The university took over excavation of the site from January through March 1928. Under their supervision, five additional pieces were discovered, adding to the growing collection, but then abruptly, the university quit. In March 1928, they walked away from the site without explanation, leaving the excavation incomplete. Bent was left to wonder what had changed. Had they found something that contradicted the artifacts' authenticity? Had internal disagreements among faculty members derailed the project? The university offered no public statement at the time, and the excavation fell silent.

Nearly a full two years later, in January 1930, the University of Arizona made its position clear. Cummings signed a four-page statement officially withdrawing the university's purchase offer, a reversal that must have been personally difficult for a man who had once declared the artifacts authentic without question and took them on tour. The university cited mounting questions about authenticity that could no longer be ignored. Professor Frank Fowler, who provided the first translation of the Latin inscriptions back in 1924, had since reversed his position entirely. His analysis revealed problems with the Latin text that suggested modern fabrication rather than ancient composition. Metallurgical testing had found that the lead was "strikingly similar to common type-metal," a synthetic alloy used in modern printing presses, not the crude smelted ore one would expect from an ancient frontier colony. Even more damning to some, one of the artifacts was physically shorter than the hole it had allegedly been found in, an impossibility if the object had truly been buried for centuries and the caliche had formed naturally around it.

The relationship between Bent and the university soured immediately. Bent felt betrayed by an institution that had promised to validate his discoveries and then abandoned him. The university, for its part, had protected its reputation by distancing itself from artifacts it now considered dubious. Cummings, who had once staked his professional credibility on the artifacts' authenticity, now found himself in the awkward position of having to explain why he had previously been wrong.

Notes and Sources

· Burgess, Don. "Romans in Tucson? The Story of an Archaeological Hoax." Journal of the Southwest, Vol. 51, No. 1 (Spring 2009), pp. 3-102.

· Fowler, Frank H. Translation of artifact inscriptions. Arizona Daily Star, 1924-1925.

· Arizona Daily Star and Tucson Citizen. Contemporary coverage, 1924-1930.

· Covey, Cyclone. Calalus: A Roman Jewish Colony in America from the Time of Charlemagne Through Alfred the Great. New York: Vantage Press, 1975.

· Yates, Donald N. The Tucson Artifacts: An Album of Photography with Transcriptions and Translations of the Medieval Latin. 2017.

Acknowledgments

A special thank you to Jace Dostal, Statewide Collections Manager at the Arizona Historical Society and the Arizona History Museum, for granting after-hours access to examine and photograph the Tucson Artifacts firsthand. Their generosity and willingness to support independent research made this article possible.